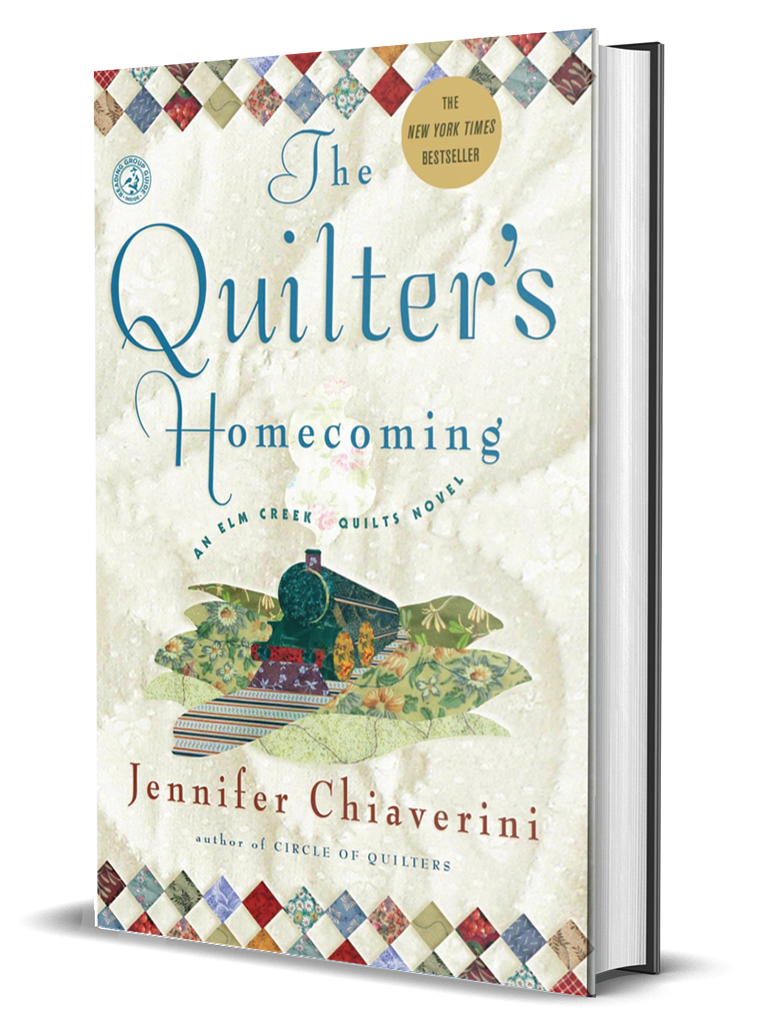

The Quilter’s Homecoming

A roaring twenties adventure unfolds in the latest novel in Jennifer Chiaverini’s Elm Creek Quilts series, “A series that neatly stitches together social drama and the art of quilting” (Library Journal).

Newly wed in a festive yet poignant ceremony at Elm Creek Manor, bride Elizabeth Nelson takes leave of her ancestral Pennsylvania home. Setting off with her husband, Henry, on the adventure of a lifetime, the couple’s trunks are packed with more than the wedding quilts Elizabeth envisions them dreaming beneath every night of their married lives. They are landowners who hold the deed to Triumph Ranch, one hundred twenty acres of prime California soil located in the Arboles Valley north of Los Angeles.

“Triumph Ranch,” says Mae, a traveling companion whom Elizabeth has let in on the promise of the Nelsons’ bright future. “That sounds like a sure thing.” But in a cruel reversal of fortune, the Nelsons arrive to the news that they’ve been had, and left suddenly, irrevocably penniless.

Hiring on as hands at the farm they thought they owned, Henry struggles mightily with his pride. Yet clever, feisty Elizabeth—drawing on her share of the Bergstrom women’s inherent economy and resilience–vows to defy fate through sheer force of will. As her life intertwines with Rosa Diaz Barclay, native to the Arboles Valley and a fellow quilter, their blossoming friendship sheds light on many secrets that have kept these quilters and their families from their rightful homes.

When Elizabeth discovers in her cabin quilts belonging to Rosa’s mother, she sees in their exquisite patterns a misplaced legacy, of love, land, and family. But her newfound understanding of the burden of loss that Rosa shares with the mysterious Lars Jorgensen—and why they dare to shed it–places her in mortal danger. Only by stitching the rift between the past and the future can the inhabitants of Triumph Ranch hope to live in peace alongside history.

Read an Excerpt from The Quilter’s Homecoming

1924

As her father’s car rumbled across the bridge over Elm Creek and emerged from the forest of bare-limbed trees onto a broad, snow-covered lawn of the Bergstrom estate, Elizabeth Bergstrom was seized by the sudden and unshakeable certainty that she should not have come to this place. She should have stayed in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to help her brother run the hotel, even though business invariably slowed during the holiday week. Or she should have offered to help care for her sister’s newborn twins. Even celebrating Christmas alone would have been preferable to returning to Elm Creek Manor. Her lifelong feelings of warmth and comfort toward the family home had suddenly given way to dread and foreboding. She would have to pass the week next door to Henry, knowing that he was near, and waiting in vain for him to come to her.

As Elm Creek Manor came into view, Elizabeth watched her father straighten in the driver’s seat, his leather-gloved fingers flexing around the steering wheel of the new Model T Ford, an unaccustomed look of ease and contentment on his face. He never drank at Elm Creek Manor, nor in the days leading up to their visits, which made Elizabeth wonder why he could not abstain in Harrisburg as well. Apparently he craved his brothers’ approval more than that of his wife and children, not that anyone but Elizabeth ever complained about his drinking.

“We’re almost home,” Elizabeth’s father said. Her mother responded with an almost inaudible sniff. It irked her that after all these years, her husband still referred to Elm Creek Manor as home, rather than their stylish apartment in the hotel her father had turned over to their management upon their marriage. Second only to her father’s flagship hotel, the Riverview Arms was smartly situated on the most fashionable street in Harrisburg, just blocks from the capitol building. It was a good living, much more reliable and lucrative than raising horses for Bergstrom Thoroughbreds. On his better days, George remembered that, but his insistence upon calling Elm Creek Manor “home” smacked of ingratitude.

But in this matter, if nothing else, Elizabeth understood her father. Of course Elm Creek Manor was home. The first Bergstroms in America had established the farm in 1857 and ever since, their family had run the farm and raised their prizewinning horses there, building on to the original farmhouse as the number of their descendents grew. They had lived, loved, argued, and celebrated within those gray stone walls for generations. But it was her father’s fate to fall in love with a girl who loved the comforts of the city too much to abandon them for life on a horse farm. He could not have Millie and Elm Creek Manor both, so he accepted his future father-in-law’s offer to sell his stake in Bergstrom Thoroughbreds and invest the profits in the Riverview Arms. Still, though he had sold his inheritance to his siblings, Elizabeth’s father would always consider Elm Creek Manor the home of his heart.

And so would she, Elizabeth told herself firmly. Though Elm Creek Manor would never belong to her the way it would her cousins, every visit would be a homecoming for as long as she lived. She would not mourn for what was lost, whether an inheritance sold off before it could pass to her, or the love of a good man whose affection she had taken for granted.

Her father parked in the circular drive and took his wife’s hand to help her from the car. Elizabeth climbed down from the back seat unassisted. A host of aunts, uncles, and cousins greeted them at the door at the top of the veranda. Uncle Fred embraced his younger brother while dear Aunt Eleanor kissed Elizabeth’s mother on both cheeks. Aunt Eleanor’s eyes sparkled with delight to have the family reunited again, but she was paler and thinner than she had been when Elizabeth last saw her, at the end of summer. Aunt Eleanor had heart trouble and had never in Elizabeth’s memory been robust, but she was so spirited that one could almost forget her affliction. Elizabeth wondered if those who lived with her daily were oblivious to how she weakened by imperceptible degrees.

Suddenly Elizabeth’s four-year-old cousin, Sylvia, darted through the crowd of taller relatives and took hold of Elizabeth’s sleeve. “I thought you were never going to get here,” she cried. “Come and play with me.”

“Let me at least get though the doorway,” said Elizabeth, laughing as Sylvia tugged off her coat. She had hoped to linger long enough to ask Aunt Eleanor—casually, of course—if she had any news of the Nelson family, but Sylvia seized her hand and led her across the marble foyer and up two flights of stairs to the nursery before Eleanor could even give her aunt and uncle a proper greeting.

Elizabeth would have to wait until supper to learn no one had seen Henry Nelson since the harvest dance in early November, except to wave to him from a distance as he worked in the fields with his brothers and father. Elizabeth feigned indifference, but her heart sank at the thought of Henry with some other girl on his arm—someone pretty and cheerful who didn’t spend half her time in a far distant city writing teasing letters about all the fun she was having with other young men. It was probably too much to hope Henry had danced only with his sister.

By the next morning Elizabeth had persuaded herself that she didn’t care how Henry might have carried on at some silly country dance. After all, since they had said good-bye at the end of the summer, she had attended many dances, shows, and clubs, always escorted by one handsome fellow or another. Her mother worried that she was running with a fast crowd, but her father, who should have known better since his own hotel had a nightclub, assumed Elizabeth and her friends passed the time together as his own generation had—in carefully supervised, sedate activities where young men and women congregated on opposite sides of the room unless prompted by a chaperon to interact. Elizabeth’s mother had a more vivid imagination, and it was she who waited up for her youngest daughter with the lights on until she was safely tucked into bed on Friday and Saturday nights.

Every summer, Elizabeth surprised her mother by willingly abandoning the delights of the city for Elm Creek Manor. Millie, oblivious to the appeal of the solace and serenity of the farm, always expected Elizabeth to put up more of an argument. Elizabeth certainly did about everything else. She wanted to bob her hair and wear dresses with hemlines up to her knee. She plastered her bedroom walls with magazine photographs of Paris, London, Venice, and other places she was highly unlikely to visit, covering up the perfectly lovely floral wallpaper selected by Millie’s mother when the hotel was built. She chatted easily with young men, guests of the hotel, before they had been properly introduced. Millie shook her head in despair over her daughter’s seeming indifference to how things looked, to what people thought. Why should anyone believe she was a well-brought up girl if she didn’t behave like one?

Yet every year as spring turned to summer, Elizabeth found herself longing for the cool breeze off the Four Brothers Mountains, the scent of apple blossoms in the orchard, the grace and speed of the horses, the awkward beauty of the colts, the warmth and affection of her aunts and uncles and grandparents. She felt at ease at Elm Creek Manor. Her meddling mother was far away. She was in no danger of walking into a room to find her father passed out over a ledger, an empty brandy bottle on the desk. There was only comfort and acceptance and peace. And Henry.

Once he had only been Henry Nelson from the next farm over, a boy more her brother’s friend than her own. All the children played together, Bergstroms and Nelsons meeting at the flat rock beneath the willow next to Elm Creek after chores were done and running wild in the forests until they were called home for supper. They met again after evening chores and stayed out well after dark, playing Hide and Seek and Ghost in the Graveyard. One hot August night on the eve of her return to the city, Elizabeth, her brother Lawrence, Henry, and Henry’s brother climbed to the top of a haystack and lay on their backs watching the night sky for shooting stars. One by one the other children crept off home to bed, but Elizabeth felt compelled to stay until she had counted one hundred shooting stars. Secretly, she had convinced herself that if she could stay awake long enough to count one hundred stars, her parents would decide that they could stay another day.

She had only reached fifty-one when Lawrence, sat up and brushed hay from his hair. “We should go in.”

“If you want to go in, go ahead. I’ll come when I’m ready.”

“I’m not letting you walk back alone in the dark. You’ll probably trip over a rock and fall in the creek.”

The darkness hid Elizabeth’s scarlet flush of shame and anger. Lawrence never made any effort to disguise his certainty that his youngest sister would fail at everything she tried. “I will not. I know the way as well as you.”

“I’ll walk back with her,” said Henry.

Lawrence agreed, glad to be rid of the burden, then he slid down from the haystack and disappeared into the night.

Elizabeth counted shooting stars in indignant silence.

“Thank you,” she said, after a while. She lay back and gazed up at the starry heavens, hay prickling beneath her, warm and sweet from the sun. After a time, Henry’s hand touched hers, and closed around it. Warmth bloomed inside her, and she knew suddenly that after this summer, everything would be different. Henry had chosen her over her brother. Henry was hers.

She was fourteen.

After that, whenever Henry came to Elm Creek Manor, Elizabeth knew she was the person he had come to see. They began exchanging letters during the months they were separated, letters in which each confided more about their hopes and fears than either would have been able to say aloud. Whenever they reunited after a long absence, Elizabeth always experienced a fleeting moment of shyness, wondering if she should have told him about her dreams to visit Paris and London and Venice, her longing to leave the stifling streets of Harrisburg for the rolling hills and green forests of the Elm Creek Valley, her shame and embarrassment when her father stumbled through the hotel lobby after returning home from his favorite speakeasy, her frustration when the rest of the family turned a blind eye. But Henry never laughed at her or turned away in disgust. In time, he became her dearest confidante and closest friend.

As the years passed, Elizabeth wondered if he would ever become more than that. He never drowned her in flattery the way other young men did; in fact, he was so plainspoken and solemn she often wondered if he cared for her at all. Sometimes she teased him by describing the parties she attended back home, the flowers other young men brought her, the poems they sent. She casually threw out references to the movies she had seen in one fellow’s company or another’s, the dances she enjoyed, how Gerald preferred the foxtrot but Jack was wild about the Charleston and Frank seemed to consider himself another Rudolph Valentino the way he danced the tango. She hoped to provoke Henry into making romantic gestures of his own, or at least to do something that might indicate a hidden reservoir of jealousy.

In her most recent letter, she had described a Christmas concert she had attended with a young man whose determination to marry her had only increased after she declined his first proposal. She had worn a blue velvet dress with a matching cloche hat; her escort had given her a corsage with three roses and a ribbon the exact shade of her dress. They had traveled in style in his father’s new Packard. The next day, their photo appeared on the society page of the Harrisburg Patriot above a caption that declared them the most handsome couple in attendance. Elizabeth included the newspaper clipping in her letter and asked Henry for his opinion: “Do you think this will encourage him to think of us as a couple? I should discourage him, but he’s such a sweet boy I hate to seem unkind. I imagine many girls are eventually won this way. Persistence is admirable in a man. If he doesn’t become impatient waiting for me, maybe someday I will come to think of him as more than a friend.”

Satisfied, she sent off her letter and awaited a declaration of Henry’s true feelings by return mail.

It never came.

As the days passed, she began to worry that instead of stirring him into action, she had driven him away. Henry was, after all, a practical man. He would not pursue a lost cause, and she had all but declared the inevitability of her marriage to another more persistent, more expressive man. Henry had endured her teasing stoically through the years, but to repay him with musings that she might fall in love with someone else might, possibly, have been going too far.

Henry had never said he loved her. He had made her no promises. He had never kissed her and rarely held her hand except to help her jump from stone to stone as they crossed Elm Creek at the narrows, or to assist her onto her horse when they went riding. She had it on very good authority that he had not sat around pining for her at that Harvest Dance. How dare he end a ten-year friendship and five-year correspondence when she quite reasonably asked his opinion about the man who seemed most interested in marrying her? He ought to be flattered that she thought so highly of his opinion, especially since he seemed to lack any romantic instincts whatsoever. She would have done better to consult Lawrence.

Henry had given up too easily. If he loved her, he would have written back. He would have been waiting for her on the front steps of Elm Creek Manor to demand that she turn down Gerald or Jack or any other fellow who came too close. He would have done something.

He hadn’t, and that told her the truth she did not want to know.

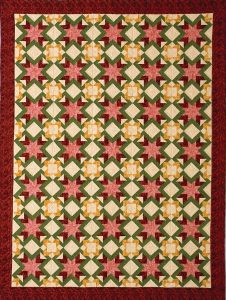

On the day before Christmas Eve, Elizabeth tried to lose herself in the joyful anticipation of the holidays. She played with little cousin Sylvia, threaded needles for Great-Aunt Lucinda as she sewed a green-and-red Feathered Star quilt, and helped Aunt Eleanor and the other Bergstrom women make delicious apple strudel as gifts for neighbors. Perhaps she should offer to take the Nelsons’ to them at Two Bears Farm on the chance that she might see Henry—but what then? How pathetic she would seem, hoping to win him back with pastry. It was very good pastry, but even so. She had her pride.

She was reading a Christmas story to Sylvia when a cousin came running to the nursery to announce that Elizabeth had a visitor. She almost knocked Sylvia out of the rocking chair in her haste to see who had come.

She hurried downstairs to find Henry in the kitchen talking companionably with her father and Uncle Fred. Her heart quickened at the sight of him, taller and more handsome than she remembered, fairer and slighter of frame than the Bergstrom men but with the hardened muscles and callused hands of a farmer. She was pleased to see he had since summer shaved off his seasonal mustache because she had never liked the way it hid the curve of his mouth. He smiled warmly at her, but she was struck by a newfound resolve in his eyes.

She knew at once that he had come to tell her he had fallen in love with someone else.

He invited her to go for a walk. Together they crossed the bridge over Elm Creek, passed the barn, and strolled along the apple grove, the trees bare-limbed and bleak against the gray sky. “What did you think of my last letter?” Elizabeth she asked when she could endure exchanging pleasantries no longer. “You never answered, unless your reply was lost in the mail.”

He was silent for a moment; the only sound was the crunching of their boots upon snow and the far-off caw of a crow. “I’m always glad to get your letters. I’m sorry I didn’t have a chance to write back. I’ve been busy with … some business matters.”

She smiled tightly. December was not usually a busy time around Two Bears Farm. “I asked for your opinion and I was counting on you to offer it.”

“I wasn’t sure what you were asking,” said Henry. “Do I think this friend of yours considers you two a couple? I’d bet on it, if you haven’t told him otherwise. Do I think you should discourage him? That depends.”

“It depends?” Elizabeth stopped and looked up at him. “It depends on what?”

“Do you want him to think you’re his girl or not? I never thought you were the type to marry a fellow because he wore you down, but if you are, maybe you should save him the time and trouble and marry him now.”

“Thank you for the suggestion,” said Elizabeth. She resumed walking, faster now, to put distance between them. “I’ll consider it.”

Henry easily caught up to her. “It wasn’t a suggestion.”

“Then what do you think?”

“Do you love him?”

“He asked me to marry him, and I refused, didn’t I?”

Henry caught her by the elbow. “That doesn’t answer my question. Do you love him?”

“No,” Elizabeth burst out. “I don’t love him, but at least I know how he feels about me, which is more than I can say about you.”

She did not expect to see Henry again, but he returned the next afternoon. By that time, most of her anger had abated. Though and the memory of her outburst and subsequent flight embarrassed her, she was determined not to apologize. She agreed to another walk, mostly out of curiosity. She had puzzled too long over the mystery of Henry’s feelings to send him away when he had apparently decided to divulge them.

He waited until they had crossed the bridge, out of earshot of both the house and the barn—unless they shouted, which was perhaps not out of the question. “I thought you knew I loved you.”

The gracelessness of his declaration sparked her anger. “How would I know, since you’ve never told me?”

“Would I write to you for five years if I didn’t love you? Would I come to Elm Creek Manor and see you every day you’re here?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“No, I wouldn’t,” he said emphatically, and Elizabeth knew it to be true. Another man might, but not Henry.

“Well, say it, then,” she told him.

He hesitated. “Why do I have to say it?”

“Because I need to know. Because you never lie, and if you say you love me straight out, I’ll have no choice but to believe you.”

He shrugged. “All right, then, I love you.”

Elizabeth nearly laughed, incredulous. “Is that the best you can do?”

“What else do you want me to say?”

“I’ve received four proposals—five, counting yours—and I have to say that this one was by far the least romantic. It might very well be the least romantic proposal of all time.”

“I wasn’t proposing. I was only trying to tell you that I love you.”

“Oh.” All the blood seemed to rush to Elizabeth’s face. “Oh. I didn’t mean—”

“Elizabeth, wait.” His voice was low and gentle, with a trace of embarrassment. “I’m coming to that part.”

She took a deep breath, ducked her chin into the collar of her coat, and shrugged, waiting for him to continue.

Henry took a thick envelope from his overcoat pocket. “I know you want to see the world. I know you wish you had land to call your own the way your aunt and uncle have Elm Creek Manor. I know you’re tired of your father’s hotel and of Harrisburg.” He thrust the envelope into her hand. When she just stared at it, he said, “Go on. Open it.”

She withdrew several sheets of thick paper, folded into thirds, and three photographs of an arid landscape of rolling hills dotted with clusters of oaks. She unfolded the papers, and as she scanned the first, Henry said, “Yesterday I told you I couldn’t answer your letter because I was occupied with some business. That’s the title to a cattle ranch in southern California.”

“The Rancho Triunfo,” Elizabeth read aloud. “You bought a ranch?”

“With every cent I’ve earned and saved since I was twelve years old. It’s about 45 miles north of Los Angeles. They say it’s like paradise, Elizabeth. Summer all year around, orange trees growing in the backyard—”

“It’s so far away.” And he had purchased the ranch without knowing whether she would want to go with him.

“Aren’t you always saying you want to leave Harrisburg?”

“Well, yes, but…” She had wanted to see the world and then come home to Elm Creek Manor. She never meant to stay away forever. “It’s on the other side of the country.”

“That’s the point.” Henry took her hands, crumpling the papers between them. “If you’ll marry me, I want to give you land of your own in the most beautiful part of the country I could find. If you won’t marry me, I want to put a continent between me and the chance I might ever see you in the arms of another man.”

Elizabeth felt breathless, lightheaded. As far as she was concerned, the most beautiful part of the country was right here, all around them. “What about Two Bears Farm? What will your parents think?”

“They have my brothers and sister to help them work the place and take it over for them one day. If I go, there will be one less person arguing for a piece of the same pie.”

And what of her family? Her mother and father expected her to marry a nice young man from Harrisburg who would come to work for her father in the family business. That was what her mother had done. Millie had shrieked in outrage when Elizabeth refused Gerald’s proposal. Gerald, who would fit so neatly into Millie’s plans for the hotel—and who drank nearly as much as her father and seemed constitutionally incapable of fidelity.

It was Henry Elizabeth wanted, although when she had imagined them together it had been at Two Bears Ranch, so close to Elm Creek Manor that it was almost as good as coming home. A ranch in southern California might be beautiful, but it would not be home.

But Henry was going, with or without her.

“Yes,” she told him softly. “I’ll marry you.”

He kissed her. The papers and photographs fell to the snowy ground, forgotten.

As Elizabeth had expected, her parents were dismayed to hear of their plans to move so far away. Millie could not disguise her anger that they had come to inform them of a decision already made, and not to seek advice and permission. George did not share his wife’s outrage, but admitted surprise that the prudent, steadfast Henry had acted so impulsively. “If you’re tired of farm life, you can come and work for me,” he offered. “I wanted to open a second hotel, and with you to help me, I could do it. It would be advantageous to both of us. Why go to the ends of the earth when you can make a decent living here?”

“I don’t intend to make only a decent living, sir. I intend to make a fortune.”

Henry spoke in such frank seriousness that Elizabeth could not help but believe him, but her father looked dubious. “A man doesn’t become a farmer to get rich.”

“Your grandfather did, sir.”

Elizabeth’s father smiled grudgingly. “That was a very different time. There are fortunes to be made every day, but not in farming, not anymore. The land isn’t worth what it used to be. My brothers have prospered because they raise prize horses. They cater to wealthy customers, and I can tell you those customers aren’t farmers. The place for an enterprising young man these days is business.”

Henry shook his head. “I intend to raise cattle, sir, not corn, not oats. I’ll be raising beef. All those wealthy businessmen who buy your Bergstrom Thoroughbreds want beef for their tables. Providing it will make me a rich man.”

Elizabeth’s father sighed, knowing the argument was lost before it had begun. “Farming is the only industry I can think of riskier than opening a new hotel across the street from your strongest competitor. If you come work for me, you’ll still make your fortune. It may take time, but you’ll get there.”

“With all due respect, sir,” said Henry carefully, “and I do value your opinion, but I could never live away from the land.”

Elizabeth’s father, who had given up his share of the Bergstrom land for a love that had not flourished with the passing of time, nodded and said no more, except to offer the couple his blessing.

When the family gathered for Christmas Eve supper the next evening, Elizabeth’s father announced their engagement. Everyone but little Sylvia welcomed the news with great joy, which made it more difficult to announce their plans to move away. The family accepted the couple’s decision with surprise, but steadied themselves with the knowledge that most Bergstroms who left the Elm Creek Valley eventually returned.

Henry’s family was far less sanguine. His sister, Rosemary, broke down in tears and begged him to reconsider. His brothers, who had assumed he would always be there to help them run the farm, voiced cautious support, shot through with shock and betrayal. His father was concerned that his ordinarily prudent son had purchased land without examining it firsthand, but after he studied their documents and photographs, he admitted everything looked to be in order. If the land was indeed as the agent had described it, Henry had made a sound investment, a sensible purchase.

But Henry’s mother took Elizabeth aside. “You can still talk him out of this,” she beseeched in a whisper. “Henry adores you. He will stay here if he knows that’s what you want.”

“I’m afraid it’s too late for that,” Elizabeth told her gently. “I don’t think he could get out of the sale even if he wanted to.”

What she did not say was that despite the small seeds of doubt Henry’s father had planted with his concerns about the sight-unseen purchase, Elizabeth had no intention of talking Henry out of it. She had become as eager as Henry to embark on their adventure, and in idle moments she would take out the photographs, search them for tiny details she had previously overlooked, and murmur, “Triumph Ranch.” The very name rang with promise.

Elizabeth had little time for romantic musings, for there was much to do before the wedding. The Pittsburgh land broker from whom Henry had purchased the ranch assured him that the former owners would be willing to remain on the ranch and tend the livestock until the end of April, but he could make no guarantees after that. At first, Henry suggested he and Elizabeth leave the week after New Year’s and marry when they arrived in California, but Elizabeth firmly refused. Her family put great stock in propriety and tradition, and she would not deny them the pleasure of a traditional Bergstrom wedding.

The scant three months of preparations raced by in a blur of dress fittings, china pattern selections, and private lectures from all of her aunts, including her unmarried Great-Aunt Lucinda, about what she could expect from married life. Some of their advice was amusing, but when the lessons dismayed and alarmed her, she allowed her mind to wander. Hadn’t she already learned everything she needed to know about being a good wife by watching her mother, grandmothers, and aunts?

When the time came to pack for their journey west, the enormity of their undertaking began to sink in. She felt almost as if she and Henry were among the early pioneers, setting out for the west with grand dreams to meet an unknown fate, uncertain whether they would ever return home. Silently she chastised herself for such foolish wrries, for so much homesickness before they even left Pennsylvania, and this from the girl who all her life had longed to see the world. Once she and Henry were established, they would surely be able to leave the Rancho Triunpho in the care of trusted ranch hands long enough for a visit home. Still, she did not know how soon a return trip might come, and she had to swallow a lump in her throat every time she thought of spending years without seeing Elm Creek Manor and those who lived there.

She took comfort in the handmade gifts the Bergstrom women gave to her as the wedding approached. In addition to lovely new clothes, they made her several quilts to use in her new home. Great-Aunt Lydia doubted that quilts would be necessary in so warm a place as southern California, but Aunt Eleanor declared that they would be a beautiful touch of home nonetheless. One of Elizabeth’s favorites was a bridal quilt in the Double Wedding Ring pattern, embellished with beautiful floral appliqués. All the women of the family had sewn together the arcs and wedges of the pieced rings, and whenever Elizabeth looked upon the quilt she recognized the work of individual quiltmakers: Great-Aunt Lucinda’s precise piecing, Aunt Eleanor’s intricate appliqué, Aunt Lydia’s painstaking stipple quilting, her grandmother’s perfectly mitered binding. As the finest quilt she owned, she should have decided to save it for company, but as soon as she saw it, she decided it must grace the bed she would share with Henry.

As lovely as the bridal quilt was, a second quilt was somehow more precious to her, even though it was only a sturdy scrap quilt meant for everyday use. Great-Aunt Lucinda had sewn it in the evenings after the day’s work was done, rocking in her favorite chair in the parlor and hiding the pieces whenever Elizabeth entered the room. Elizabeth pretended not to notice since it was obvious Great-Aunt Lucinda intended the quilt to be a surprise, but her curiosity was piqued and she could not resist a little surreptitious observation of her aunt at work. One day a few weeks before the wedding, Sylvia gave Elizabeth the perfect opportunity. She had just been scolded by her father for some minor offense intended to prevent the marriage—telling Henry she hated him, perhaps, or pretending she had the plague so the house would be quarantined—and she had sought out the comfort of Great-Aunt Lucinda’s lap for her sulk. Elizabeth listened just beyond the doorway as Great-Aunt Lucinda told Sylvia about the quilt, made in a pattern of concentric rectangles and squares, one half of the block light colors, the other dark in the fashion of a Log Cabin block.

“This pattern is called Chimneys and Cornerstones,” Great-Aunt Lucinda explained. “Whenever Elizabeth sees it, she’ll remember our home and all the people in it. We Bergstroms have been blessed to have a home filled with love from the chimneys to the cornerstone. This quilt will help Elizabeth take some of that love with her.”

Silence prompted Elizabeth to draw closer and peek into the room. Sylvia was watching Great-aunt Lucinda as she ran her finger along a diagonal row of red squares, from one corner of the block to its opposite. “Do you see these red squares? Each is a fire burning in the fireplace to warm Elizabeth after a weary journey home.”

“You made too many,” said Sylvia, counting. “We don’t have so many fireplaces.”

“I know,” said Lucinda, smiling in amusement. “It’s just a fancy. Elizabeth will understand. But there’s more to the story. Do you see how one half of the block is dark fabric, and the other is light? The dark half represents the sorrows in a life, and the light colors represent the joys.”

“Then why don’t you give her a quilt with all light fabric?”

“I suppose I could, but then she wouldn’t be able to see the pattern. The design appears only if you have both dark and light fabric.”

“But I don’t want Elizabeth to have any sorrows.”

“I don’t either, love, but sorrows come to us all. But don’t worry. Remember these?” Lucinda touched several red squares arranged diagonally across one block. “As long as these home fires keep burning, Elizabeth will always have more joys than sorrows.”

Little Sylvia’s brow furrowed as she studied the quilt. Suddenly she brightened. “The red squares are keeping the sorrow part away from the light part.”

“That’s exactly right,” Great-Aunt Lucinda praised her. “What a bright little girl you are.”

Pleased, Sylvia snuggled closer to her great-aunt. “I still don’t like the sorrow part.”

“None of us do. Let’s hope that Elizabeth finds all the joy she deserves, and only enough sorrow to nurture an empathetic heart.”

When Great-Aunt Lucinda gave Elizabeth the quilt the day before the wedding, she said nothing of the quilt’s symbolism or how much Elizabeth would be missed. Lucinda had stitched her farewells and hopes for her grandniece into the quilt, and as Elizabeth held the soft folds of cloth to her heart, she understood everything Lucinda could not say. For a fleeting moment she feared that leaving Pennsylvania would be a terrible mistake, bringing down upon her all the sorrows that Great-Aunt Lucinda wanted the fires of home to protect her from. Then she thought of Henry, and how that in all her hopes of future happiness, she imagined herself by his side. She knew she could not stay behind.

She wrapped their new china in the precious quilts for protection and placed them in her sturdiest trunk, a gift from Lawrence. Then, at last, all was ready.

The wedding itself passed in a blur. She had always heard that a wedding day was the happiest in a young woman’s life, but she was sure she would remember hers only in glimpses: her mother helping her arrange her golden hair into long corkscrew curls swept back from her face by her headpiece and veil, her father walking her down the aisle of the same church her parents had married in, Henry’s encouraging smile as she murmured her vows, a whirl of celebration back at the manor. She could not swallow more than a few bites of the delicious feast her mother and aunts had prepared, but her first dance with Henry as husband and wife filled her with the warmth of pure happiness. She knew with a certainty she could not explain that she and Henry would weather whatever storms came their way—not that they were likely to face many in sunny southern California.