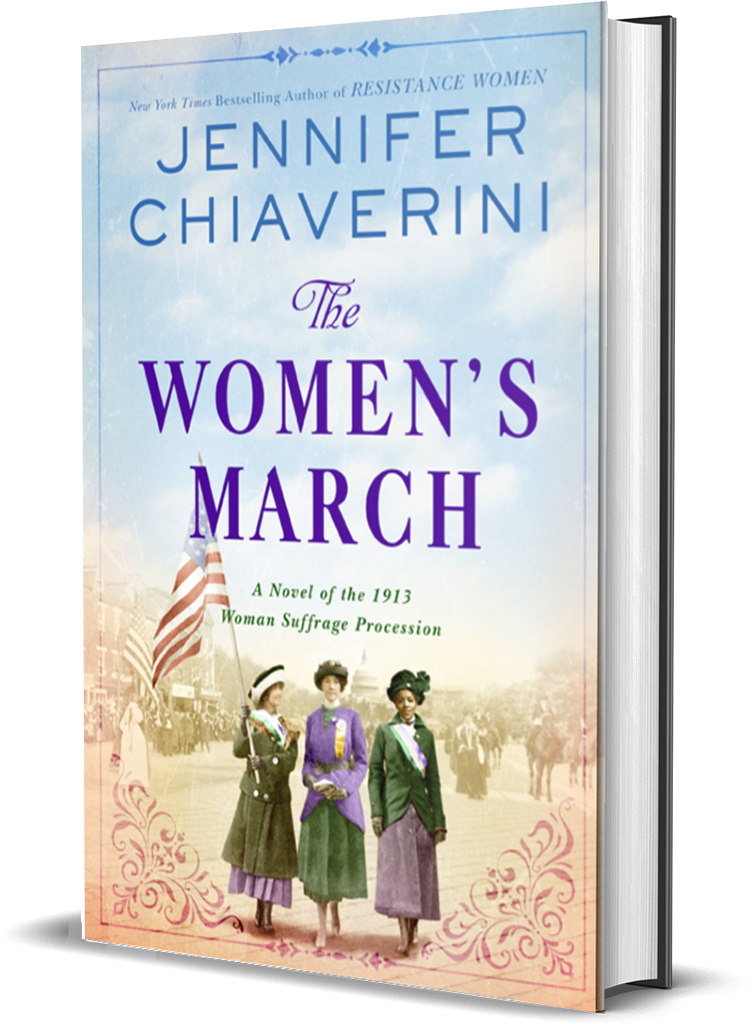

The Women’s March

“Chiaverini offers an impassioned account that pulls readers into the organization, staging, and aftermath of this historic protest, making the details feel freshly alive. . . This politically aware novel about a historic quest for democratic justice compels readers to contemplate everything that has and hasn’t changed regarding voting rights and gender and racial equality.”

—Booklist

New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Chiaverini returns with The Women’s March, an enthralling historical novel of the woman’s suffrage movement inspired by three courageous women who bravely risked their lives and liberty in the fight to win the vote.

Twenty-five-year-old Alice Paul returns to her native New Jersey after several years on the front lines of the suffrage movement in Great Britain. Weakened from imprisonment and hunger strikes, she is nevertheless determined to invigorate the stagnant suffrage movement in her homeland. Nine states have already granted women voting rights, but only a constitutional amendment will secure the vote for all.

Joining the march is thirty-nine-year-old New Yorker Maud Malone, librarian and advocate for women’s and workers’ rights. The daughter of Irish immigrants, Maud has acquired a reputation—and a criminal record—for interrupting politicians’ speeches with pointed questions they’d rather ignore.

Civil rights activist and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett resolves that women of color must also be included in the march—and the proposed amendment. Born into slavery in Mississippi, Ida worries that white suffragists may exclude Black women if it serves their own interests.

On March 3, 1913, the glorious march commences, but negligent police allow vast crowds of belligerent men to block the parade route—jeering, shouting threats, assaulting the marchers—endangering not only the success of the demonstration but the women’s very lives.

Inspired by actual events, The Women’s March offers a fascinating account of a crucial but little-remembered moment in American history, a turning point in the struggle for women’s rights.

Click here to pre-order autographed copies from Books & Company!

Praise for The Women’s March

Read an Excerpt from The Women’s March

Prologue

October 19, 1912

Brooklyn, New York

Wilson

“On behalf of the Democratic Campaign Committee of Kings County,” declared the tall, fair-haired Scotsman behind the podium at center stage, his powerful brogue rising dramatically over the cheers of the assembled throng, “it is my great honor and privilege to welcome the former president of Princeton University, the current governor of New Jersey, and the future president of the United States, the honorable Woodrow Wilson!”

The cheers rose to a roar as Wilson emerged from the curtained wing and crossed the stage to meet Chairman McLean at the podium, the smells of tobacco, damp wool, and perspiration wafting from the audience almost as blinding as the glare of the footlights. The venerable theater was packed to the rafters, attesting to McLean’s ability to muster up voters as well as Wilson’s own renown as an orator and statesman. When he and his entourage had arrived at the Brooklyn Academy of Music not long before, their driver had been obliged to halt half a block away, the automobile’s progress impeded by a crowd of hundreds holding tickets aloft and pushing their way into the packed front vestibule. A team of police officers had been obliged to clear a path from the automobile to a side entrance. As Wilson shook McLean’s hand and murmured his thanks, he noted with satisfaction that those same eager men now filled every seat and spilled over into the aisles, applauding, waving their hats in the air, shouting his name.

He hoped their enthusiasm would carry them to the polls come November 5—not only these wildly applauding men, but also vast droves of voters of a similar temperament, all dissatisfied with the incumbent, hankering for change, but wary of radicals. Wilson was their man.

He took the podium, raised his hands, and nodded to one section of the house and then another, modestly acknowledging their ardent welcome while also seeking order, mildly surprised to see a few ladies scattered among the gentlemen. As soon as his audience had settled down, he launched into his stump speech—well practiced by now, so late in the campaign, but even more urgent than when he had first announced his candidacy. Their democracy was failing ordinary Americans, he warned. All governmental power was monopolized by a few corrupt men who controlled the system utterly and for their own benefit. Yet an even greater monopoly, rarely mentioned elsewhere in the campaign, threatened to—

“What about votes for women?” someone interrupted from the balcony. It was a woman’s voice, full and musical, with an Irish lilt.

Wilson abruptly fell silent as heads craned and murmurs arose, a ripple of confusion and annoyance and disgust. Stepping out from behind the podium and approaching the front of the stage, Wilson scanned the upper seats until his gaze fell upon a fair, auburn-haired woman dressed in a purple shirtwaist and a hat adorned with a yellow feather. She awaited his response, her gaze fixed on his, determined and utterly devoid of deference. And yet there was something warm and appealing in her expression too; slender and apparently in her mid-thirties, she would probably be quite pretty if she smiled.

“What is it, madam?” he called up to her over the grumbles of the crowd.

“You say you want to destroy monopolies.” Her eyebrows rose, signifying the innocence and eminent rationality of her query. “I ask you, what about woman suffrage? Men have a monopoly on the vote. Why not start there?”

The audience snickered. “Sit down,” someone groused loudly from the back.

“Woman suffrage, madam, is not a question for the federal government,” Wilson explained patiently, clasping his hands behind his back. He felt almost as if he were back at Bryn Mawr, addressing a class of lovely but tragically uncomprehending female pupils. “It is a matter for the states. As a representative of the nationalparty, I cannot speak to this issue.”

“But I address you as an American, Mr. Wilson,” the woman persisted. “Since you seek to govern all these united states, surely you can tell us where you stand.”

The crowd’s growing dissatisfaction manifested in mutters and glares, in impatient shifting in seats. “Let us not be rude to any woman,” Wilson reminded them, silently adding, No matter how unwomanly she may be. To the offender herself, he replied firmly, “I hope you will not consider it a discourtesy if I decline to answer those questions on this occasion.”

“But I do consider it discourteous, Governor, and worse.” She put her head to one side, curious. “Unless you mean to say that you have no opinion whatsoever?”

“Throw her out!” a deep voice bellowed just beyond the footlights, cutting off Wilson’s reply.

A few rows behind that fellow, another man rose from his seat, cupped his hands around his mouth, and shouted toward the balcony, “Why don’t you go to your own meeting, girlie?”

A roar of laughter followed.

“Go home and mind the babies!”

“Put her out! Where are the police?”

Wilson could have answered that. From his ideal vantage point, he easily spotted three grim-faced, gray-uniformed officers working their way down the aisles of the crowded balcony toward the woman. With them was a man in a well-cut dark suit, perhaps in his fifties, with Germanic features and an imperious manner, as if he were accustomed to having his orders obeyed. He said something to the woman and made a cutting gesture with his forearm; she threw him a retort over her shoulder. Then her gaze returned to Wilson’s and held it, despite the jostling of the increasingly disgruntled men surrounding her.

This could get ugly, Wilson realized. It would play very badly in the press.

“Now, gentlemen, let us remain civil,” he urged, concealing his own rising annoyance. Why did she not simply sit down? “I’m sure the lady will not persist when I positively decline to discuss the question now.”

He gestured for her to take her seat—and yet still she stood, waiting for him to satisfy her question, as if he had not made it perfectly clear that no answer would be forthcoming. Just then the policemen reached her. To Wilson’s consternation, they seized her by the arms and waist, lifted her roughly, and wrestled her from the hall through a fire exit against a backdrop of jeers, hisses, and blistering insults.

“Gentlemen, it is very much against my wishes that the lady has been ejected,” Wilson protested, although he doubted he could be heard above the din. “I respect her right to put questions to me, however inopportune.”

Inopportune? Better he should say potentially disastrous. He of all men did not quake before difficult questions, but he simply could not afford to answer that particular one, not with Taft and Roosevelt and Debs snapping at his heels, ready to drag him down at the first sign of weakness. Of course he had an opinion on woman suffrage, one shared by the vast majority of southern men: he was definitely and irreconcilably opposed to it. The social changes woman suffrage would entail would not justify whatever small gains might be accomplished. But he could not say so aloud, not with the press standing by with pencils hovering over pads and so many voters yet undecided. Better to evade the question by insisting it was a matter of states’ rights, beyond the purview of a presidential candidate.

“I would like to have your attention,” Wilson addressed the restless audience, raising his voice but refusing to shout, “while I recover the thread of what I was saying.”

The crowd soon settled down, and Wilson continued his speech precisely where he had left off, describing what he considered to be the worst monopoly of all, the influence of powerful interests upon the government. Thereafter the only interruptions were welcome bursts of applause.

When he finished speaking, he barely had time to take a few dignified bows before the candidate for lieutenant governor replaced him at the podium. A moment later his aides were hustling him off the stage, into his topcoat, and outside to the automobile, which waited, engine rumbling, to speed them off to his next engagement.

“Who was that obnoxious woman?” he asked irritably as they settled themselves in the vehicle and the driver swiftly set off for Carnegie Hall, across the East River and north to midtown Manhattan. Women who spoke in public gave him a chilled, scandalized feeling. Thankfully, his own wife and daughters understood that a woman’s place was in the home.

“That harridan? Maud Malone,” one of his aides replied. “She’s a militant suffragist librarian and a notorious heckler. Just last week she interrupted Governor Johnson’s speech at a Bull Moose meeting. She interrupted Roosevelt on the night before the primaries.”

Wilson was tempted to ask how Roosevelt had responded, but he could well imagine how the former Republican president, now leader of the breakaway self-proclaimed Progressive Party, would have appeased the harasser with promises he was powerless to fulfill.

“What will become of this Miss Malone?” Wilson asked. The type of woman who took an active part in suffrage agitation was totally abhorrent to him, and yet he did not like to see any lady so roughly handled.

“She’ll be escorted to the nearest police station and arraigned, I imagine.” His aide offered a reassuring grin. “Don’t worry about her. She’ll pay her bail and be back home with her piles of books and innumerable cats by midnight.”

The youngest of Wilson’s aides chuckled, but the most experienced of the three did not even smile. “Don’t let this incident concern you, Governor,” he said. “Miss Malone, like all those other suffragettes with a penchant for public spectacle, is an irritant, nothing more. She doesn’t even have the power to vote against you.”

Yes, there was that. Wilson settled back against the soft leather seat and turned his thoughts from the unsettling Irishwoman to his next speech. He was due to take the stage again in less than an hour, and with only seventeen days until the election, he could not allow himself to be distracted by pretty hecklers and their ludicrous propositions.