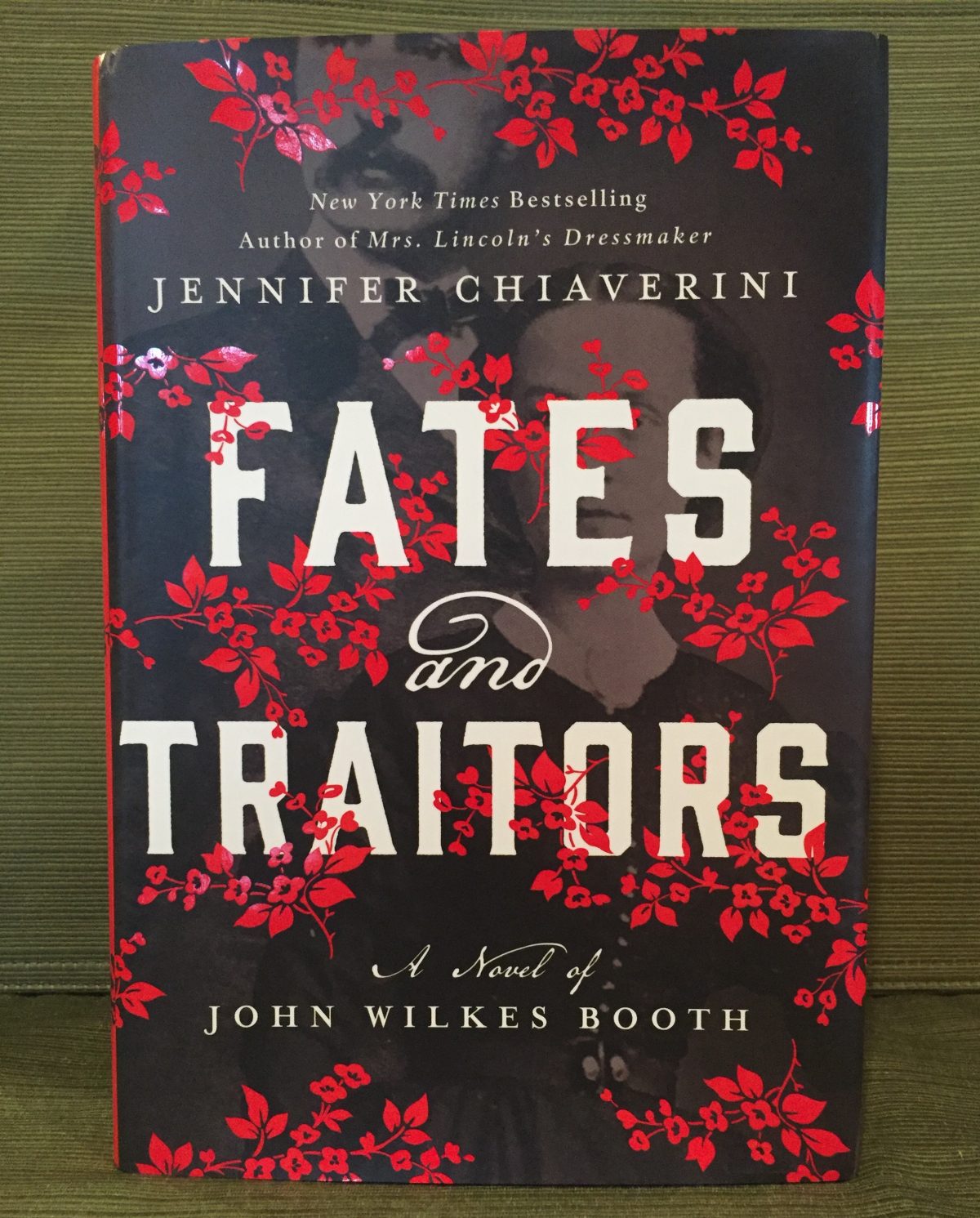

Since Shakespeare was so important to this family of actors and writers, I wanted my novel to have a title inspired by Shakespeare’s plays. Julius Caesar was the clear choice, not only because of the themes of assassination and betrayal, but because the only time the three actor sons of Junius Brutus Booth ever performed together was in a production of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York on November 23, 1864.

In Act 2 Scene 3, the soothsayer Artemidorus writes a letter to warn Caesar about the plot against him. “If thou read this, O Caesar, thou mayst live,” he says as he prepares to deliver it. “If not, the Fates with traitors do contrive.” I could not help thinking that if only my four narrators had shared what each of them knew about Booth’s escalating anger and his evolving plot against the president, his intentions might have been made clear, and perhaps they could have prevented him from carrying out the assassination. But although Mary Ann and Asia were often together, and Lucy exchanged at least a few letters with members of Booth’s family, the four of them were never all together, and this conversation never took place. I found this idea of a tragedy that could have been prevented if only a warning had been delivered in time to be very compelling.

Then too we have that word, “Traitors.” John Wilkes Booth and Mary Surratt certainly didn’t consider themselves to be traitors but patriots, although history sees them differently. As for “Fates,” throughout Booth’s life there were visions and prophecies that indicated he was fated for either glory or a violent, notorious end. Was it Booth’s fate to become the most notorious assassin in American history, or could he have chosen another way?