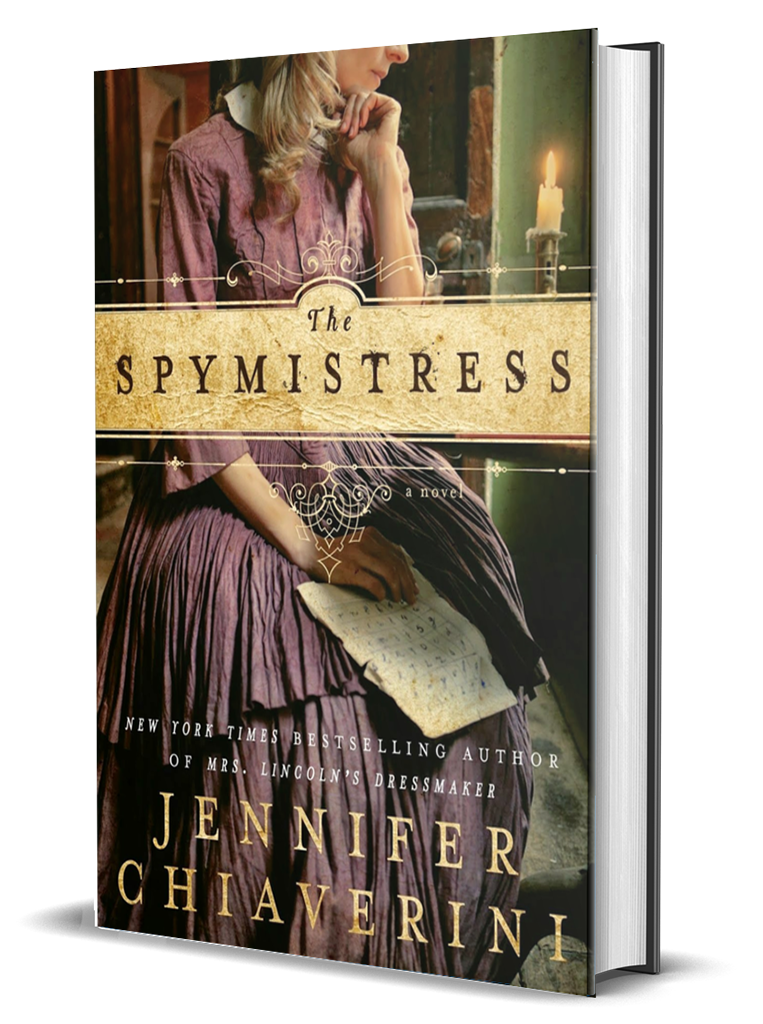

The Spymistress

“Peppered with interactions between Lizzie and well-known historic figures, Jennifer Chiaverini’s latest bestseller will thrill Civil War buffs and anyone who loves reading about American history and the contribution of women to the momentous events that formed this country.”

—Bookreporter

New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Chiaverini is back with another enthralling historical novel set during the Civil War era, this time inspired by the life of “a true Union woman as true as steel” who risked everything by caring for Union prisoners of war—and stealing Confederate secrets.

Born to slave-holding aristocracy in Richmond, Virginia, and educated by northern Quakers, Elizabeth Van Lew was a paradox of her time. When her native state seceded in April 1861, Van Lew’s convictions compelled her to defy the new Confederate regime. Pledging her loyalty to the Lincoln White House, her courage would never waver, even as her wartime actions threatened not only her reputation but also her life.

Van Lew’s skills in gathering military intelligence were unparalleled. She helped to construct the Richmond Underground and orchestrated escapes from the infamous Confederate Libby Prison under the guise of humanitarian aid. Her spy ring’s reach was vast from clerks in the Confederate War and Navy departments to the very home of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Although Van Lew was posthumously inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame, the astonishing scope of her achievements has never been widely known. In Chiaverini’s riveting tale of high-stakes espionage, a great heroine of the Civil War finally gets her due.

Read an Excerpt from The Spymistress

April 1861

The Van Lew mansion in Richmond’s fashionable Church Hill neighborhood had not hosted a wedding gala in many a year, and if the bride-to-be did not emerge from her attic bedroom soon, Lizzie feared it might not that day either.

Turning away from the staircase, Lizzie resisted the urge to check her engraved pocket watch for the fifth time in as many minutes and instead stepped outside onto the side portico, abandoning the mansion to her family, servants, and the apparently bashful bridal party ensconced in the servants’ quarters. Surely Mary Jane wasn’t having second thoughts. She adored Wilson Bowser, and just that morning she had declared him the most excellent man of her acquaintance. A young woman in love would not leave such a man standing at the altar.

Perhaps Mary Jane was merely nervous, or a button had come off her gown, or her flowers were not quite perfect. As hostess, Lizzie ought to go and see, but a strange reluctance held her back. Earlier that morning, when Mary Jane’s friends had arrived—young women of color like Mary Jane herself, some enslaved, some free—Lizzie had felt awkward and unwanted among them, a sensation unfamiliar and particularly unsettling to experience in her own home. None of the girls had spoken impudently to her, but after greeting her politely they had encircled Mary Jane and led her off to her attic bedroom, turning their backs upon Lizzie as if they had quite forgotten she was there. And so she was left to wait, alone and increasingly curious.

Grasping the smooth, whitewashed railing, Lizzie gazed out upon the sun-splashed gardens, where the alluring fragrance of magnolia drifted on the balmy air above the neatly pruned hedgerows. Across the street, a shaft of sunlight bathed the steeple of St. John’s Episcopal Church in a rosy glow like a benediction from heaven, blessing the bride and groom, blessing the vows they would soon take. It was a perfect spring day in Richmond, the sort of April morning that inspired bad poetry and impulsive declarations of affection best kept to oneself. Lizzie could almost forget that not far away, in the heart of the city, a furious debate was raging, a searing prelude to the vote that would determine whether her beloved Virginia would follow the southern cotton states out of the fragmenting nation.

Despite the clamor and frenzy that had surged in Richmond in the weeks leading up to the succession convention, Lizzie staunchly believed that reason, pragmatism, and loyalty would triumph in the end. Unionist delegates outnumbered secessionist fire-eaters two to one, and Virginians were too proud of their heritage as the birthplace of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison to leave the nation their honored forebears had founded.

Still, she had to admit that John Lewis’s increasing pessimism troubled her. Mr. Lewis, a longtime family friend serving as a delegate from Rockingham County, had been the Van Lews’ guest throughout the convention, and his ominous reports of shouting matches erupting in closed sessions made her uneasy. So too did the gathering of a splinter group of adamant secessionists only a block and a half away from the Capitol, although outwardly she made light of the so-called Spontaneous People’s Convention. “How can a convention be both spontaneous and arranged well in advance, with time for the sending and accepting of invitations?” she had mocked, but the tentative, worried smiles her mother and brother had given her in reply were but a small reward.

Although Lizzie managed such shows of levity of time to time, she could not ignore the disquieting signs that the people of Richmond were declaring themselves for the Confederacy in ever greater numbers. Less than a week before, when word reached the city of the Union garrison’s surrender at Fort Sumter in Charleston, neighbors and strangers alike had thronged into the streets, shouting and crying and flinging their hats into the air. Impromptu parades had formed and bands had played spirited renditions of “Dixie” and “The Marseillaise.” Down by the riverside at the Tredegar Iron Works, thousands had cheered as a newly-cast cannon fired off a thunderous salute to the victors. Lizzie had been dismayed to see, waving here and there above the heads of the crowd, home-sewn flags boasting the South Carolina palmetto or the three stripes and seven stars of the Confederacy. But when the crowd marched to the governor’s mansion, instead of giving them the speech they demanded, John Letcher urged them to all go home.

Lizzie had been heartened by the governor’s refusal to cower before the mob, and she prayed that his example would help other wavering Unionists find their courage and remember their duty. But the next day, word came to Richmond that President Lincoln had called for seventy-five thousand militia to put down the rebellion—and Virginia would be required to provide her share. Many Virginians who had been ambivalent about secession until then had become outraged by the president’s demand that they go to war against their fellow southerners, and they defiantly joined the clamor of voices shouting for Virginia to leave the Union. John Minor Botts, a Whig and perhaps the most outspoken and steadfast Unionist in Richmond politics, had called the mobilization proclamation “the most unfortunate state paper that ever issued from any executive since the establishment of the government.”

But would it prove to be the straw that broke the camel’s back? Lizzie could not allow herself to believe it.

“Rational men will not cave in to the demands of the mob,” Lizzie had argued to Mr. Lewis that very morning. Like herself, he was a Virginia native, born in 1818, and a Whig. Unlike her, he was married, had children, and could vote. “They will heed the demands of their consciences and the law.”

A few crumbs of Hannah’s light, buttery biscuits fell free from Mr. Lewis’s dark beard as he shook his head. “A man who fears for his life may be willing to consider a different interpretation of the law.”

At that, a shadow of worry had passed over Mother’s face. “You don’t mean there have been threats of violence?”

“It pains me to distress you, but indeed, yes, and almost daily,” Mr. Lewis had replied. “Those of us known to be faithful to the Union run a gauntlet of insults, abuse, and worse whenever we enter or depart the Capitol.”

“Goodness.” Mother had shuddered and hunched her thin shoulders as if warding off an icy wind. Petite and elegant, with gray eyes and an enviably fair complexion even at sixty-three years of age, she was ever the thoughtful hostess. “You must allow us to send Peter and William along with you from now on. They will see to your safety.”

“Thank you, madam, but I must decline. I won’t allow my enemies to believe they’ve intimidated me.”

“When the vote is called, wiser heads will prevail,” Lizzie had insisted, as much to reassure herself and Mother as to persuade Mr. Lewis. “Virginians are too proud a people to let bullies rule the day.”

“As you say, Miss Van Lew. Nothing would please me more than to be proven wrong.”

Remembering his somber words, Lizzie gazed off to the west toward the political heart of the city, scarcely seeing the historic church, the gracious homes, and the well-tended gardens arrayed so beautifully before her. Instead she imagined the view from the Capitol gallery, where she had often sat and observed the machinery of government, and she wished she could be there to witness the contentious debate for herself. Of course, that was not possible. The gallery had been shut to visitors for the closed session, and Lizzie could not miss Mary Jane’s wedding. She could only wait for news and hope that her faith in the men of Virginia had not been misplaced.

The scrape of the door over stone warned her that she was no longer alone. “Your mother has come down,” announced her sister-in-law, Mary, in a peevish tone Lizzie found particularly grating.

“Very good,” she said briskly, turning around. “And the bride?”

“I haven’t seen her and I haven’t inquired.” Mary spoke airily and tossed her wheat brown hair, but her frown betrayed her annoyance. “I don’t understand why the family is obliged to make such a fuss over a colored servant. A wedding service at St. John’s and a luncheon on our own piazza! Why shouldn’t they exchange vows at the African Baptist church or whatever it’s called, you know the one I mean—”

“I do know the one you mean.” Lizzie fixed her with a level gaze and a sweet smile. “It’s a charming church, but Mary Jane is family—”

“Oh, Lizzie, don’t be sentimental. She’s not, not really.”

“Mary Jane is family,” Lizzie repeated, coolly emphatic. “And as a member of the Van Lew family, she has every right and expectation to be married at St. John’s.”

Mary shook her head, exasperated. “You have the oddest notions.” Mary was sixteen years younger than Lizzie and a good two inches taller, with delicate features, wide brown eyes, and a petulant pout gentlemen seemed to find adorable. Lizzie’s brother certainly had, until he had discovered that her pout heralded spats and tantrums, after which he had learned to dread its appearance.

Lizzie managed a tight smile. “Yes, I do. I am, after all, the resident eccentric. Please don’t feel obliged to join in our celebration if it offends your sense of propriety. I’d be delighted to ask Caroline to send up a plate to your room, a safe distance away from our fuss and frivolity.”

If Caroline included a tumbler of whiskey on the tray, Lizzie thought witheringly, Mary would be happier still.

“I’ll ask Caroline myself,” Mary retorted, and flounced back inside. “It would be just like you to forget, and allow me to go hungry.”

Through the open door, Lizzie watched Mary storm past Mother, who stood in the foyer clad in her shawl and bonnet. Mother’s gaze followed her daughter-in-law until Mary disappeared down the hall, and then she turned to Lizzie, eyebrows raised. Lizzie smiled weakly and shrugged, but Mother was not fooled, and lingering on the portico would only delay the well-deserved reprimand.

“Lizzie, dear,” Mother chided gently when Lizzie joined her inside. “What did you do this time?”

“I merely pointed out that Mary needn’t attend the wedding feast if she finds it so terribly inappropriate.”

“You spoke without thinking.”

“Yes, I realize that now. I should have added that my nieces are still very much welcome.”

“That’s not what I meant and you know it.” Mother shook her head, her expression both fond and regretful. “I believe sometimes you go out of your way to provoke her. For your brother’s sake, won’t you try harder to practice forbearance? You know how much it pains John to see the women he loves at odds.”

Lizzie did know. She drew herself up, inhaling deeply and quashing the pangs of guilt that pricked her whenever she earned her mother’s disapproval. She wished she could be as good and gracious as Mother, but what seemed to come naturally to Mother required constant effort for Lizzie. “For John’s sake and for yours, I will try harder. I will even apologize to Mary when I next see her.”

“Apologize?” A smile quirked in the corners of Mother’s mouth. “She may faint from shock.”

“Then I’ll be sure to guide her to the sofa before I speak.”

A sudden burst of laughter from above drew their attention, and in unison they glanced to the top of the stairs, where they discovered Mary Jane surrounded by her attendants.

“At last, the bride descends,” Lizzie remarked.

“And none too soon,” said Mother, sighing with delight. “Oh, isn’t she lovely?”

She was indeed, but Lizzie found herself suddenly too moved to say so. Mary Jane’s smile was radiant, her coffee-and-cream complexion luminous as she descended the grand staircase in a gown of ivory linen trimmed with flounces of eyelet lace at the hem, throat, and wrists. One of Mary Jane’s friends must have lent her the amber necklace and earbobs adorning her graceful head and neck, for Lizzie did not recognize them. Her cheeks were flushed with excitement, but her gaze was calm and steady, preternaturally wise for a young woman of scarcely twenty-five.

By the time the bridal party reached the foot of the stairs, Lizzie had found her voice. “My dear Mary Jane.” She hurried to embrace her. “You are a vision. You look exactly as a bride should.”

“Thank you, Miss Lizzie.” Mary Jane’s voice was low and mellifluous, but her smile, as ever, hinted at sardonic mischief. She was well-practiced at using that smile to her benefit—and at concealing it where it might bring her unwanted attention. “I hope Wilson thinks so.”

“He’s a fool if he don’t,” one of her friends declared, provoking laughter from the others.

Wilson Bowser was no fool, Lizzie reflected as her brother John appeared to escort the bride across the street to the church. Wilson was freeborn, tall and dark skinned, with the broad chest and strong shoulders earned from years of working on the railroad. He loved Mary Jane, and better yet, he seemed to respect her. He was not the man Lizzie would have chosen for Mary Jane, but he was a good, decent man, and as likely to be faithful as any other. Lizzie’s greatest concern about the match was that Mary Jane, who had been educated in the North and had worked as a missionary in Liberia, might eventually become disenchanted with Wilson, who had no education to speak of and had never traveled more than ten miles from Richmond. But who could say whether such disparities doomed a marriage to failure? After all, on the day her brother and Mary had wed, they had seemed an ideal match despite the difference in their ages. Regrettably, a mere six years later, anyone could see that their marriage was utterly joyless, except for the two delightful daughters their union had produced.

If a match that had once seemed so promising could take such a dismal turn, who could predict whether Mary Jane and Wilson would end up content or miserable? No one could, certainly not a spinster of forty-three who had last enjoyed the heady flush of romance more than two decades before.

Absently, Lizzie touched the silver locket at her throat, then slipped her hand into her pocket, finding reassurance in the familiar weight and coolness and patterns of delicate engraving of her pocket watch, another gift. They were her most cherished possessions—mementoes of her youth, treasures from a faded age.

Perhaps Mary was right to call her sentimental.

Beckoned from their tasks by the sound of voices, the servants had joined the family and the wedding party in the foyer—Caroline, the cook, who assured Mother that all was ready for the luncheon; Hannah Roane, the nurse, who had brought her two young charges clad in their Sunday best, although their mother was nowhere in sight; Hannah’s grown sons, William the butler and Peter the groom; Judy, who was officially Mother’s maid though she assisted all the Van Lew women with their dresses and hair; and old Uncle Nelson, proud of his title of gardener although in recent months his rheumatism had kept him from all but the lightest work. The Van Lews employed other servants, of course, kitchen assistants and laundresses and housecleaners, but they lived out, and since the bride knew them only in passing, it had not seemed appropriate to invite them.

Together the cheerful party left the mansion and strolled down the block and across the street to St. John’s Episcopal Church. The front doors had been adorned with magnolia blossoms, and inside the vestibule, more friends and family of the happy couple waited to greet the bride and her retinue. Others had seated themselves in the rows of wooden pews, and as Lizzie escorted her mother to their places, she glanced down the aisle and suppressed a smile at the sight of Wilson standing up front between the minister and his Best Man, rocking back and forth on his heels, his hands clasped behind his back—and, if Lizzie were not mistaken, a sheen of nervous perspiration on his brow. Searching for his bride, he happened to look Lizzie’s way, and when she gave him an encouraging smile, he managed a perfunctory nod and a weak grin of his own.

Within moments his anxious demeanor gave way to elation as the organist struck up a triumphant march and Mary Jane came down the aisle on Uncle Nelson’s arm. Lizzie and Mother exchanged a look of surprise—the wedding had begun and John and the girls had not joined them in their family pew. Perhaps Annie and Eliza had gotten out of hand and he was sorting it out, or perhaps he had been called to the hardware store on urgent business, or perhaps—Lizzie’s heart thumped—perhaps Mr. Lewis had sent unfortunate news from the Capitol. But peering over her shoulder, she glimpsed John seated in the back with little Annie on his lap and baby Eliza beside him in Hannah’s arms.

Suddenly Mother rested her hand upon hers, so Lizzie quickly turned round to face front again, but her mother’s apprehensive frown immediately told her that some other worry troubled her, not her daughter’s fidgeting in church.

“Perhaps they should have married another day,” Mother whispered, something she never did after the minister stood at the pulpit.

“Why not today?” Lizzie whispered back, and with a teasing smile, added, “‘Marry on Monday for health, Tuesday for wealth, Wednesday the best day of all—’”

“No, that’s not what I meant.” Mother’s gaze was fixed on the bride and groom, who were gazing at one another with shining eyes, their hands clasped, fingers intertwined. “Should they marry today, in such troubled times, with the vote for secession coming any moment? It seems an inauspicious day, bearing ill omens for their future happiness.”

“No, Mother,” Lizzie said, her voice low and gentle. “You have it quite in reverse. Think instead of what this wedding portends for the vote. Today, in this sacred place, where Patrick Henry declared ‘Give me liberty or give me death,’ we celebrate union.”

A warm smile lit up Mother’s soft, lined face, and she thanked Lizzie with a gentle squeeze of her hand.