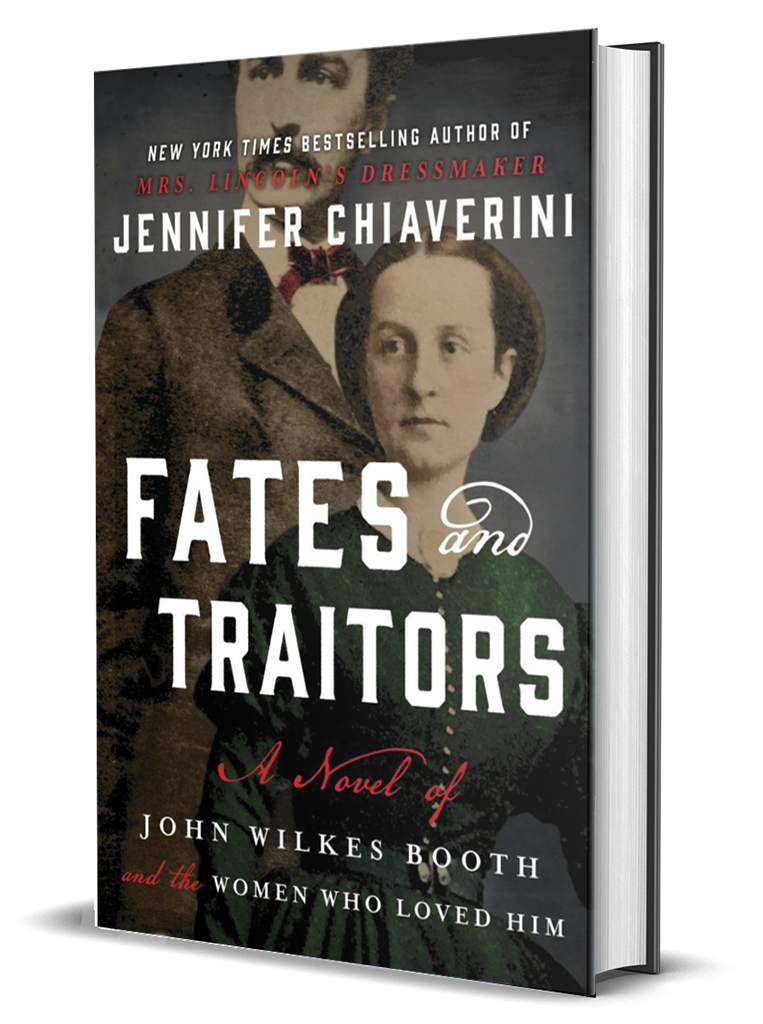

Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker

“[An] absorbing stand-alone historical novel. Taking readers through times of war and peace as seen through the eyes of an extraordinary woman, the author brings Civil War Washington to vivid life through her meticulously researched authentic detail. Chiaverini’s characters are compelling and accurate; the reader truly feels drawn into the intimate scenes at the White House.”

—Library Journal

In a life that spanned nearly a century and witnessed some of the most momentous events in American history, Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was born a slave. She earned her freedom by the skill of her needle, and won the friendship of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln by her devotion. In her sweeping historical novel, Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker, New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Chiaverini illuminates the extraordinary relationship the two women shared, beginning in the hallowed halls of the White House during the trials of the Civil War and enduring almost, but not quite, to the end of Mrs. Lincoln’s days.

Elizabeth Keckley made her professional reputation in Washington, D. C., making expertly fashioned dresses for the city’s elite, among them Mrs. Jefferson Davis and Mrs. Robert E. Lee. In March 1861, Mrs. Lincoln chose her from among numerous applicants to be her personal “modiste,” responsible for creating the First Lady’s beautiful gowns and dressing her for important occasions. In this role, Elizabeth Keckley was quickly drawn into the intimate life of the Lincoln family, a clear-eyed but compassionate witness to events within the private quarters of the White House.

Ever loyal to the Union, Elizabeth Keckley hid her fears when her only son, George, enlisted with the 1st Missouri Volunteers, and his courage in battle inspired her to bold new endeavors. When tens of thousands of former slaves sought refuge in Washington, she cared for them in their squalid camps, taught them sewing and other necessary skills, founded the Contraband Relief Association—to which Mary Todd Lincoln was a generous contributor—and worked tirelessly to raise money so that the struggling freedmen could embrace their newfound liberty. All the while, Elizabeth Keckley supported the First Lady through years of war, political strife, and devastating personal losses, even as she endured heartbreaking tragedies of her own.

Even more daring, Keckley not only made history, but wrote it, in her own words. The publication of her memoir, Behind the Scenes: Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, placed her at the center of a scandal she never intended. The sensational fallout distanced the longtime confidantes, and for the rest of her days, Elizabeth Keckley sought redemption through living an exemplary life.

Impeccably researched and thoroughly engrossing, Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker renders this singular story of intertwining lives in rich, moving style.

Praise for Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker

Read an Excerpt from Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker

November 1860–January 1861

On Election Day, Elizabeth Keckley hurried home from a midafternoon dress fitting to the red brick boardinghouse on Twelfth Street where she rented two small rooms in the back. Although she never failed to carry her license attesting to her status as a freedwoman whenever she ventured out, on that day of the presidential election of 1860 she was eager to be safely indoors well before curfew. The city hummed with breathless excitement even though the white citizens of Washington City, District of Columbia, were not enfranchised to vote. In this, the capital’s colored residents, both slave and free, were their equals, although Elizabeth prudently refrained from remarking upon this similarity to the wives of the city’s social and political elite for whom she sewed the beautiful gowns they wore to balls and levees and receptions. Her patrons were united in their suspicion of and disdain for the Republican candidate, a lawyer from Illinois they disparaged as an unpolished rube from the West and a radical abolitionist. They disagreed, however, on which of his three rivals ought to succeed President Buchanan, who, if ineffectual, had at least done their home states and the South’s “peculiar institution” no enduring harm.

If a spontaneous parade sprang up and turned into a riot, as happened far too often those days, Elizabeth wanted to be well away from the furor. Already the streets were filling with men hurrying from tavern to hotel for news of the election, gathering on corners with like-minded fellows and glaring across the way at their rivals, crowding anxiously around the doors of the telegraph office on Fourteenth Street although the returns wouldn’t be in for hours yet. Many folks had obviously been enjoying the free whiskey dispensed by the various political clubs that dotted the blocks near the White House, and from time to time their bursts of raucous laughter drowned out even the unceasing clip-clop of horses’ hooves and the more distant whistles of passing trains. As she made her way home, Elizabeth tightened her grip on her sewing basket and kept her bearing serene and composed, flinching only once, when a young man wearing a campaign button boasting a tintype of Mr. Breckinridge jostled her in his haste to reach the bulletin board outside the National Hotel.

She breathed a sigh of relief when she reached her own quiet neighborhood, a haven in what had been an unfamiliar city only months before. Earlier that spring, she had come to Washington City after a few failed weeks in Baltimore, where her struggle to find work convinced her to seek her fortune elsewhere. Not long before that, she had lived in St. Louis, where, after years of toiling and saving, she had purchased her freedom and her son’s. Now George was a student at Wilberforce University in Ohio, and she was a successful mantua maker, a businesswoman with an admirable reputation, independent and free. She could more easily bear the miles separating her from her only child knowing that he was acquiring the education she herself had always longed for and had been denied, and that no man could claim him as property ever again.

Virginia Lewis, her landlady and dear friend, must have seen her approach through the front window, for she met her at the door. “What’s the news?” she asked, breathless, studying her expression as if to read the answer there. “I know how your ladies talk. If anyone knows what’s happening, they would.”

“I’m afraid they don’t know any more than we do.” Elizabeth set down her sewing basket and unwrapped herself from her shawl. “Nothing’s changed from what we heard this morning. Mr. Lincoln’s favored to win, but we won’t know for a fact until they count the ballots.”

“I suppose your ladies wouldn’t care much for a President Lincoln.”

“Not one bit. Most of their husbands like Mr. Breckinridge, and so they do likewise. A few of them like Mr. Bell too.” Elizabeth lowered her voice conspiratorially. “As for Mr. Lincoln, they fear he wants to free all the slaves.”

They shared a laugh. “Well, then, God bless him,” declared Virginia. “If that’s true, I pray he wins.”

Elizabeth nodded, but private doubts troubled her. No matter what the Southern partisans inhabiting the city said about Abraham Lincoln, as far as she knew, he had never promised to end slavery, only to keep it from spreading. But even if he had placed his hand on a Bible and declared himself a staunch abolitionist, her few months in Washington had taught her that candidates often made promises that they found impossible to keep after taking office. Whatever Mr. Lincoln’s intentions, and whether they boded ill or good for Elizabeth and the Lewises and other colored folk, when Mr. Lincoln’s people swept into the city to take over, most of Mr. Buchanan’s would be swept out, among them the husbands of several of her best patrons. She could only hope that enough of them would remain behind to keep her business thriving.

It was perhaps too much to hope that the new First Lady would have a taste for finery, and that Elizabeth might somehow attract her notice.

It was well after midnight when she was startled awake by the sounds of shouting on the streets outside, of jubilant songs and speeches, and soon thereafter, of the firing of pistols and shattering of windows. She sat up in bed and strained her ears in the darkness, sifting sense from the jumble of noise and fury until she understood that the votes had been counted, the result announced.

Abraham Lincoln would become the sixteenth president of the United States.