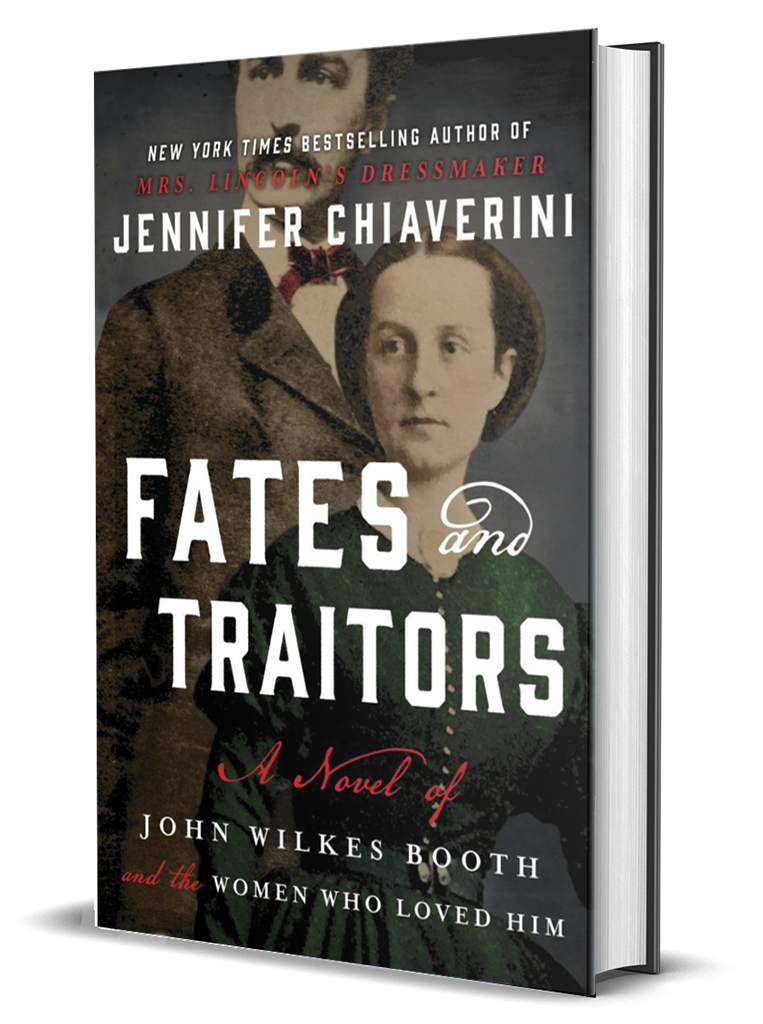

Fates and Traitors

“In her latest novel, Fates and Traitors, Jennifer Chiaverini once again demonstrates her masterful ability to bring history to life..With her varied and well-drawn ensemble of female narrators, Chiaverini spins a rich and suspenseful tale, shedding new light on America’s most notorious assassin—and the women who loved him.” —Allison Pataki, New York Times Bestselling author of Sisi: Empress On Her Own

The New York Times bestselling author of Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker returns with a riveting work of historical fiction following the notorious John Wilkes Booth and the four women who kept his perilous confidence.

John Wilkes Booth, the mercurial son of an acclaimed British stage actor and a Covent Garden flower girl, committed one of the most notorious acts in American history—the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

The subject of more than a century of scholarship, speculation, and even obsession, Booth is often portrayed as a shadowy figure, a violent loner whose single murderous act made him the most hated man in America. Lost to history until now is the story of the four women whom he loved and who loved him in return: Mary Ann, the steadfast matriarch of the Booth family; Asia, his loyal sister and confidante; Lucy Lambert Hale, the senator’s daughter who adored Booth yet tragically misunderstood the intensity of his wrath; and Mary Surratt, the Confederate widow entrusted with the secrets of his vengeful plot.

Fates and Traitors brings to life pivotal actors—some willing, others unwitting—who made an indelible mark on the history of our nation. Chiaverini portrays not just a soul in turmoil but a country at the precipice of immense change.

Praise for Fates and Traitors

Read an Excerpt from Fates and Traitors

John

1865

If it be aught toward the general good,

Set honor in one eye and death i’ th’ other,

And I will look on both indifferently,

For let the gods so speed me as I love

The name of honor more than I fear death.

—William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2

A sound in the darkness outside the barn—a furtive whisper, the careless snap of a dry twig underfoot—woke him from a fitful doze. His left leg throbbed painfully, not only the tender, swollen tissue nearest the fracture in the bone but everything from ankle to knee, the muscles sore from too many days in stirrups, the skin chafed raw from the reluctant doctor’s hasty splint. Grimacing, every movement a new torment, he propped himself up on his elbows and strained his ears to listen.

There—a low whisper, quick footfalls, and, more distantly, the jingle of spurs. And then, incautiously, two men arguing in hushed voices, one commanding, one pleading. A flicker of candlelight illuminated the shallow depression beneath the door of the tobacco barn, and—he jerked his head sharply when a sudden gleam caught the corner of his eye—the glint of a lantern appeared between the slats on the opposite side.

The barn was surrounded.

Blood pounded in his ears as he inched closer to his companion, grimacing in pain as he dragged himself from his makeshift bed on the hay-strewn floor. Covering the younger man’s mouth with one hand, with the other he grasped him by the shoulder and shook him awake. “Herold,” he murmured, his gaze darting from the door to the four walls. “Wake up.”

David Herold woke with a start. “What is it, John?” he whispered hoarsely. “Is Garrett running us off after all?”

Richard Garrett, the lean, grim-faced farmer who had welcomed them into his home earlier that day, had banished them to the barn upon discovering their true identities. Adding to the insult, he had locked them in to ensure that they wouldn’t run off with the family’s horses in the night. Had Garrett betrayed them to the men now drawing the cordon tight around their refuge? When put to the test, had the Virginia farmer’s Southern sympathies given way to craven fear?

Rage flared up within John, hot and searing, only to sputter and die out, extinguished by hard, cold truth. It mattered not how their pursuers had found them, only that they had.

“The barn is surrounded,” he told Herold, his voice preternaturally calm.

Muttering an oath, Herold scrambled to sit up, his short stature and fine wisps of facial hair making him seem even younger than his almost twenty-three years. “Should we surrender before they open fire?”

“I’ll suffer death first.” John pulled Herold close and added in a voice scarcely more than a breath, “Don’t make a sound. Maybe they’ll think we aren’t here and go away.”

At that moment, the plaintive creak of hinges drew their attention to the door, which was slowly, cautiously opening. A figure stepped into the doorway, thrown into silhouette by a distant lantern. “Gentlemen, the cavalry are after you.” It was Jack Garrett, the farmer’s eldest son, Garrett’s eldest son, recently returned from the war. He had been clad in a gray Confederate uniform when they first met—had it really been only the previous afternoon?

“You’re the ones they seek.” Jack Garrett’s voice gathered strength as it probed the darkness. “You’d better give yourselves up.”

“John Wilkes Booth,” another man proclaimed, emerging in the doorway behind Jack Garrett, a candle in his fist. “I want you to surrender. If you don’t, in fifteen minutes I’ll burn the barn down around you.”

Grasping his injured leg, John drew himself up as tall as he could sit. “And who are you, sir?” he demanded, his voice ringing as it had from the stage of Grover’s Theatre, the Arch Street Theatre, the National, the Marshall, Ford’s—the scenes of his greatest triumphs. He could triumph here yet. “This is a hard case. It may be that I am to be taken by my friends.”

“I’m Lieutenant Luther Byron Baker, detective, United States Department of War, and I order you to turn your weapons over to Garrett and give yourself up.”

Herold, trembling and sweating despite the cold, took his head in his hands, moaning softly through clenched teeth. “You don’t choose to give yourself up,” he told John shakily. “But I do. Let me go out.”

“No,” John retorted, forcing his voice to remain steady, his heart thudding in time with the throbbing of his injured leg. “You shall not.”

As they argued, their voices low and heated, John’s mouth went dry and a fearful tremor seized him. He was aware of Garrett speaking over his shoulder to the other men as he backed away from the doorway, and of Herold slipping from his control. Another ten minutes and the boy’s terror would overcome him entirely. Before that moment came, John must sow enough confusion to conceal their escape, or all would be lost.

He seized Herold by the shoulder—to restrain his companion as well as to brace himself against his own rising panic. “Surely we can come to an understanding between gentlemen,” he called grandly, projecting his voice through the doorway to the officer lurking outside. “If I had been inclined to shoot my way to freedom, your candle would have made you an easy target.”

Silence followed his declaration, and as he watched, the thin light wavered, shadows shifting as Baker carried the candle away and planted it on some hillock in the yard. Boots scraping on hard packed earth alerted him to the officer’s return. “Give up your arms or the barn will be set on fire,” the lieutenant commanded. A low growl of assent revealed his companions’ numbers—a dozen at least, fully armed, no doubt, filled with misguided, righteous anger, panting to avenge their slain leader. John knew nothing would convince them that he had saved them from a tyrant.

In the diminished light, his gaze traveled the length and width of the barn, searching, hoping. There must be an escape, even now. He and young Herold could flee to Mexico, where Emperor Maximilian was offering refuge and substantial bounties to steadfast Confederates. There he would at last be proclaimed a hero, as he had not been in Maryland, Virginia, or anywhere in the ungrateful South. There, Lucy’s studies of the Spanish tongue would serve them well.

Lucy, he thought, picturing her as he had last seen her, smiling and beautiful in the dining room of the National Hotel. Sweet Lucy. What did she think of him now? Would her love remain true, or did she too abhor him? Surely he could make her understand that the fractured nation owed all her troubles to Lincoln. The country had groaned beneath his tyranny and had prayed for this end, and God had made John the instrument of His perfect wrath. How bewildering it was, in the aftermath of the deed that should have made him great, to find himself abandoned by the very people he served, in desperate flight with the mark of Cain upon him, but if the world knew his heart, if Lucy knew his heart—

His courage faltering, he forced thoughts of his beloved aside. “My good sir,” he called out, stalling for time, thoughts racing, “that’s rather rough. I’m nothing but a cripple. I have but one leg, and you ought to give me a chance for a fair fight.”

“We’re not here to argue,” Baker shouted back, anger and impatience whetting the edge of his voice. “You’ve got five minutes left to consider the matter.”

“I don’t need five minutes, Booth,” said Herold, rising, clenching his hands, pacing, his anxious gaze fixed upon the doorway. “They got us cornered. We got no choice but to give up. Don’t you see? We’ve gone as far as we can.”

John would not concede that they had, not while breath remained in his body. Again and again he tried to engage Baker in conversation, but the Yankee lieutenant would neither negotiate nor be distracted, insisting that the fugitives consider their circumstances and make their choice. Increasingly frustrated, John looked to Herold, who paced and gnawed his fingernails to the quick and would clearly be no help at all.

“Well, then,” John called to Baker almost cheerfully, “throw open the door, draw up your men in line, and let’s have a fair fight.”

“Garrett,” said another man, whose voice John had not yet heard, “gather some of those pine twigs and pile them up by the sides of the barn.”

“What does he mean?” Herold asked, panic infiltrating his voice. “What are they doing?”

“Calm yourself.” John strained his ears to detect Garrett’s retreat, and soon thereafter, returning footfalls and the sound of an armload of pine boughs falling in a pile near the door. Alarmed, he shouted, “Put no more brush there or someone will get hurt.”

“Booth.” Herold backed into the center of the barn, gaze darting wildly, hands spread as if to ward off an invisible foe. “Booth—”

“Herold, I told you—” A whiff of smoke in the air silenced him, the crackle of new flame. Quickly he discovered the source—someone had twisted hay into a makeshift wick, set it on fire, and shoved it through a crack between the boards of the barn wall. He watched, thunderstruck, as flames licked greedily at the wooden planks, steadily climbing, cutting through the shadows with garish light.

“I’m going,” Herold croaked, pale with terror. “I don’t intend to be burnt alive.”

As the younger man strode toward the door, John quickly reached out and seized the cuff of his trousers, gasping as stabbing pains shot up his broken leg. “Take another step and I’ll kill you.”

Herold gaped at him, his mouth open in a silent protest, his pouchy cheeks quivering, his face eerily young in the rising light of the blaze. Suddenly John recalled how obediently Herold had served the conspiracy over the past year, how faithfully he had served John throughout their flight from Washington—guiding him through the back woods and swamps of Maryland and Virginia, finding them safe havens with sympathetic civilians along the way, risking his life in dangerous river crossings, tending John in his infirmity. John remembered, and he regretted his cruel threat.

He must save the boy, if he could not save them both.

“Get away from me, you damned coward,” he snarled loudly for the audience outside. As Herold pulled away, John yanked him back again and added in a whisper, “When you get out, don’t tell them what arms I carry.”

Bewildered, Herold mutely nodded, stumbling backward when John released him.

“Lieutenant Baker,” John called out, “there is a man in here who wants to surrender. He is innocent of any crime.”

After a moment’s pause, Baker called back, “Pass your weapons through the door and come out with your hands in the air.”

“He has no weapons.” John coughed and waved away a tendril of smoke scented with wood and tobacco and straw. A trickle of sweat ran from his temple to his jaw. “All the arms here are mine.”

In a panic, Herold sprinted to the door, only to find it barred against him. “Let me out,” he shrieked, pounding on the door. “Let me out!”

The door swung open. A soldier ordered Herold to extend his hands, one at a time, and the moment he obeyed, someone seized his wrists and yanked him out of sight. Before the door swung shut again, John glimpsed rifles and pistols trained upon the entrance, gleaming in the light from the burning barn.

The blaze had scaled the walls and spread to the rafters, roaring and crackling and filling the air with choking smoke. Scooting away from the walls, dragging his injured leg after him, John looked about for something, anything, to put out the fire. Instead through the cracks between the wooden planks he glimpsed the pale faces of Union soldiers outside, angry and curious, emboldened by Herold’s surrender. They watched him with hungry avarice, like a vicious pack of dogs studying a cornered stag.

Resolute, he took his Spencer carbine in hand and reached for his crutch. If these were to be his last moments, he would not spend them lying in the dirty straw, helpless and despairing, so his enemies might watch him roast alive. As quickly as he dared, he pushed himself to his feet and steadied himself on the crutch.

He had nowhere to go but into the arms of his vengeful enemies.

Supporting his weight on the crutch, he made his way to the door, wincing as a shower of sparks flew too close before his face. The crutch slipped from beneath his outstretched arm as he reached for the latch, but he let it fall. He would face the soldiers standing, defiant and proud on his own two feet.

He drew himself up as he shuffled into the doorway, and raised his carbine—

And then he was lying on his face in the dirt, his head spinning, his neck trembling electrically as if in the aftermath of a lightning strike, his strong body strangely limp and heavy. He could not open his eyes, or dared not try.

He heard the faint thunder of quick footfalls, felt the strike of the soldiers’ boots on the earth transmitted through the ground to his forehead. Something warm and liquid trickled from his neck down his collar past his clavicle, over the old scar he boasted as a war wound, but when he reached up to brush the irritant away, his hand and arm did not respond. Dimly he puzzled over this oddity as the men gathered around him.

“Is he dead?” an unfamiliar voice queried, shrill with excitement. “Did he shoot himself?”

“No,” replied Lieutenant Baker. “I don’t think so. I don’t know what happened.”

John wanted nothing more than to riposte with a mocking jest, but the words eluded him, whirling beyond his fingertips like cottonwood seeds caught in a sudden gale. He felt them swirling about him, small and white and soft, thousands upon thousands, felt himself sinking into them as they mounded up around him on all sides. The crackling blaze faded, its light and sound growing faint, but the smell of scorched tobacco and ash lingered in his nostrils, a curious singularity that kept the white softness from engulfing him completely.

There were hands upon him, he realized, inquisitive and none too gentle. He had been shot, he heard someone say. They found the wound on the right side of his neck. Someone had disobeyed orders and had shot the most despised man in America, robbing the Yankees of the trial and execution they surely craved.

John felt himself rising, lifted roughly and carried away from the heat and light that flickered beyond his closed eyelids. He heard the crash of a roof falling in as he was placed on a patch of soft grass, his face turned toward the stars. Slowly at first, and then in a torrent, the blood rushed in his ears, and his head began to pound. He ached all over, his strangely heavy, frozen body sparking with pain.

He had been shot through the neck, he realized, vaguely astonished, as the last of the white softness blew away. He was probably dying.

He tried to speak, but he could manage no more than a wheeze, which was enough to draw the men closer. “Thought he was dead already,” one muttered.

“He’s on his way to dying,” said another. “Hold on, he’s trying to talk.”

“Tell—” John rasped. “Tell her—”

A slim figure bent over him, lowered an ear close to John’s mouth. “Go on.”

John took a shuddering breath through the thick fluid collecting in his throat. “Tell my mother. . .I die for my country.”

Nearby, a man cursed. Another spat in the dirt. “Tell your mother you die for your country,” the slim figure repeated slowly. “Do I have that right?”

John swallowed and tried to nod. The man nodded once and moved away.

He drifted, jolted from time to time into wakeful horror by unexpected surges of pain running the length of limbs that felt nothing else. He could not move. He struggled even to breathe. He closed his eyes to the falling ashes but could not shut his ears against the soldiers’ words. One man repeatedly insisted that John had shot himself. John wanted to set the record straight, but he found it too difficult to gather the correct words and put them down again in the proper order.

“I tell you again, that can’t be,” said Baker. “I was looking right at him when I heard the shot. His carbine wasn’t turned upon himself.”

The discussion wore on, and John felt himself succumbing to wave after wave of exhaustion. Then two other men approached and settled the matter with a revelation: a Sergeant Corbett had shot the president’s assassin. He had the spent cap and an empty chamber in his revolver to prove it.

Corbett, John thought. He knew no one by that name, could not imagine how he might have offended the man aside from killing his president and freeing him from tyranny. Perhaps this Corbett had a pretty little wife who had once waited outside a stage door to greet John with sweet blushes and flowers. He smiled and tried to offer the sergeant a gallant apology, but his lips moved without sound.

“I went to the barn.” The new voice rang with zeal. “I looked through a crack, saw Booth coming towards the door, sighted at his body, and fired.”

“Against orders,” said Baker, without rancor.

“We had no orders either to fire or not to fire,” the sergeant protested. “I was afraid he’d either shoot someone or get away.”

The lieutenant did not rebuke him.

John drifted in and out of consciousness, succumbing to exhaustion only to be choked awake when blood and fluid pooled in his throat. As the heat from the conflagration rose to a blistering intensity, the soldiers carried him from the lawn to the front porch of the farmhouse, where Mrs. Garrett had placed a mattress for him. Her cool, soft hand on his forehead revived him, and when he struggled to ask for water, she understood his hoarse request, quickly filled a dipper, and brought it to his lips. But it was no use. He could wet his tongue but he could not swallow.

He asked to be turned over, expecting a rebuff, but the soldiers complied, lifting him and placing him on his stomach. Still he could not clear his throat. Hating his helplessness, he asked to be rolled onto his side, and then the other, but that was no better. Panic and despair swept through him at the thought that he would drown in his own sick. Coughing, wrenching his head, he managed to catch the attention of the slim man who had taken his message for his mother. “Kill me,” he whispered when the man knelt beside him. “Kill me.”

“We don’t want to kill you,” said the man. “We want you to get well.”

So they could stretch his neck, no doubt. But he was already a dead man. And what, he thought wildly, had become of Herold?

The hours passed. His throat swelled, his lips grew numb. He felt himself sinking, only to revive, time and again. He wished the slim officer would sit beside him, to hear and commit to memory his last loving words for his mother. As for last words for his country, as well as for the North, the manifesto he had placed with his sister for safekeeping would have to suffice. Dear Asia, childhood playmate and lifelong confidante, who disagreed with him vehemently on almost every political matter but loved him still—she knew not what he had entrusted to her, but news of his demise would remind her of the thick envelope locked away in her husband’s safe. Asia would find his last great written work, his apologia, as well as documents and deeds and a letter for their mother.

Their mother. How grateful he was that she could not see how he suffered.

He realized he had fallen unconscious when he woke to the touch of calloused hands bathing his wounds. He had been pondering something . . . yes, his last words. In Asia’s safe, in the home she shared with her husband and children. A sudden worry seized him. Would she burn the papers, fearing they would implicate her, endanger her family? No, not loyal Asia, not the family historian who had begged their mother not to destroy their father’s letters as she had fed them into the flames. Asia would spare his writings and far from implicating her, they would exonerate her. He would have abandoned his mission rather than bring suspicion down upon any member of his family, or upon any lady—even one such as Mrs. Surratt, who had lent her tacit support to the plot by harboring many of the conspirators in her boardinghouse, by giving them an inconspicuous place to meet. But none would condemn her for that, a respectable, devout widow unaware of John’s true intentions. Of all the women who loved him—and Mrs. Surratt did love him, as one loved a comrade in arms—she alone shared his devotion to the South.

Fluid filled his throat; he choked, gasped, grew dizzy—and rallied, somehow. He wished he had not.

His thoughts turned to Lucy. He wished he could retrieve his diary from his coat pocket and gaze upon her portrait before the light faded from his eyes. He could imagine the shock and reproach in hers. She would mourn him, but in silence, lest his notoriety ruin her. He could not blame her for that. Few knew of their secret engagement, so Lucy would grieve, but in time her heart would heal, and with her ties to the assassin forgotten, she would eventually marry someone else. Someone safe, someone her parents could accept. That dull security would be John’s last bequest to her.

The sky was softening in the east when a physician came to examine him, a South Carolinian from the sound of it, unsettled by the sight of so many armed Yankees but determined to do his duty. John fought to stay conscious throughout the examination, and was rewarded with one last comedic jest when the doctor announced that he was badly injured but would survive.

If not for the smothering thickness in his chest John would have derided the fool. Throw physic to the dogs; I’ll none of it.

“But the ball passed clean through the neck,” said Baker, incredulous. “How can he live?”

Sighing in consternation, the doctor cleaned his spectacles, replaced them, bent over his patient again, and peered at the holes on either side of John’s neck. Then, straightening, he declared that closer scrutiny revealed that the shot had severed the assassin’s spinal cord. His organs were failing, one by one, and if he did not drown in his own blood and sputum first, he would slowly suffocate.

“Well,” the slim man said, “that’s it, then.”

John was powerless to resist as the slim man bent over him and briskly searched his pockets, taking from him a candle, his compass, and his diary, in which John had placed Lucy’s photograph. Before he could beg the man to let him gaze upon her image one last time, the officer was gone, taking John’s belongings with him. But would he carry John’s last message for his mother?

Agitated, John coughed and spat blood, gurgling in lieu of speech, desperate.

He thought he would suffocate before anyone responded, but then the lieutenant was at his side, frowning intently down upon him. John jerked his head twice to beckon the officer closer, and though his mouth twisted in revulsion, Baker complied, bending over and placing his ear close to John’s lips.

“Tell my mother—” He could scarce draw breath. “Tell my mother that I did it for my country—”

He could not fill his lungs; his throat constricted ever tighter. “That I die for my country.”

The sun had risen above the distant hills, harsh and unnaturally warm. He clenched his teeth, his eyes tearing against the glare until some pitying soul draped a shirt over a chair to shield his face.

He was John Wilkes Booth. If he had done wrong in ridding the world of the man who would declare himself king of America, let God, not man, judge him.

Out, out, brief candle!

Did he not have a candle in his pocket? No, the lieutenant had taken it, and Lucy’s portrait, and his diary, his apologia. But he should need no candle to see by, with the sun so hot upon his face.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.

Yes, and so he should remind the good women who had loved him, to give them some measure of peace. If he could but find pen and paper and ink, and light his candle to see by, for it had grown so dark so suddenly. . . . He strained to pat his pockets but was surprised to discover he could not move, and surprised again that he could have forgotten something so important.

Lieutenant Baker peered curiously down at him. “You want to see your hands?”

He wanted the use of them, but since he could not speak to clarify, he could only lie passively, unresisting, as the lieutenant lifted his hands up and into his line of sight. He glimpsed the tattoo he had given himself as a child, his initials etched upon the back of his left hand between his thumb and forefinger, his defiant, indelible rebuttal to all those who would deny his right to bear the proud name of Booth.

He gazed upon his hands, as limp and insensible as those of a corpse.

“Useless,” he croaked. “Useless.”

All that lives must die, passing through nature to eternity.

The world would not look upon his like again.