The Giving Quilt

“Chiaverini’s themes of love, loss, and healing will resonate with many, and her characters’ stories are inspiring.”

–Publishers Weekly

“Chiaverini delivers another satisfying Elm Creek Quilts story in the latest title in this excellent series…This volume features the series at its best, with warm, fully realized characters and powerful themes.”

—Booklist

“Why do you give?” asks Master Quilter Sylvia Bergstrom Compson Cooper in The Giving Quilt, New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Chiaverini’s artful, inspiring novel that imagines what good would come from practicing the holiday spirit, each and every day of the year.

At Elm Creek Manor, the week after Thanksgiving is “Quiltsgiving,” a time to commence a season of generosity. From near and far, quilters and aspiring quilters—a librarian, a teacher, a college student, and a quilt shop clerk among them—gather for a special winter session of quilt camp to make quilts for Project Linus.

Each quilter, ever mindful that many of her neighbors, friends, and family members are struggling through difficult times, uses her creative gifts to alleviate their collective burden. As the week unfolds, the quilters respond to Sylvia’s provocative question in ways as varied as the life experiences that drew them to Elm Creek Manor. Love and comfort are sewn into the warm, bright, beautiful quilts they stitch, and their stories collectively consider the strength of human connection, and its rich rewards.

Featuring not only well-loved characters but intriguing newcomers, The Giving Quilt will remind us all: Giving from the heart blesses the giver as much as the recipient, and while giving may not always be easy, it is always worthwhile.

Praise for The Giving Quilt

Read an Excerpt from The Giving Quilt

An empty teacup in one hand and a folder of papers tucked under her other arm, Sylvia shut the library doors and strode briskly down the hall to the grand oak staircase of Elm Creek Manor, mulling over the many tasks she had yet to complete in the solitary hour before her guests were due to arrive.

She had descended only a few steps when she was drawn from her reverie by the uncanny sensation of eyes upon her.

She paused on the landing, her grasp firm upon the carved banister worn smooth from generations of Bergstroms who had inhabited the manor before her and the many friends and guests who had resided within its gray stone walls in the decades since. She glanced warily over her shoulder, but when she saw no one—not a soul on the second-floor balcony or on the stairs climbing to the third story high above—she continued her descent, the certainty that she was being watched increasing with every step. As she crossed the foyer and headed toward the older west wing of the manor, she sensed rather than heard soft footfalls on the black marble floor behind her. Turning quickly, she glimpsed a swirl of black fabric and upraised arms and sharp white fangs an instant before her stalker shouted, “Boo!”

“Oh, my heavens!” exclaimed Sylvia, clutching the folder to her chest. “What a frightening creature!”

Four-and-a-half-year-old James frowned around a mouthful of plastic vampire fangs, his arms falling to his sides. “You weren’t scared.”

“Indeed I was,” Sylvia assured him. “Absolutely terrified.”

“No, you weren’t,” James insisted glumly, his words muffled by the plastic teeth. “You didn’t even drop your cup. It would have smashed into a hundred pieces.”

Sylvia frowned briefly at the cup that had betrayed her. “I’m sorry to disappoint you, dear,” she told the youngster. But she wasn’t very sorry, considering that the teacup was one of the few precious pieces of her grandmother’s wedding china that had not been broken or sold off long ago. She supposed she could have shrieked, thrown the folder into the air, and pretended not to enjoy James’s triumphant grin as the pages fluttered to the black marble floor like blanched autumn leaves, but her knees and back were not up to the task of crawling around to gather up the scattered pages. There were limits to the amount of terror she was willing to feign for the boy’s amusement. “You truly do make a most terrifying vampire.”

“She would’ve been more scared if you hadn’t yelled ‘Boo,’” said James’s twin sister, Caroline, stepping out from behind the draperies adorning one of the tall windows flanking the front entrance. “Vampires don’t yell ‘Boo.’”

“Zombies don’t talk at all,” James shot back, “so you should just be quiet.”

“They do too talk,” said Caroline, padding toward them in her pink ballet leotard and her mother’s black leather coat. Sylvia eyed the hem as it skimmed the floor and wondered if Sarah was aware that her favorite autumn coat had apparently found its way into the twins’ bin of dress-up clothes. “Zombies say, ‘Braaaaiiinnssss.’ Anyway, I can talk all I want because I’m not a zombie anymore.”

“What are you, then?” Sylvia inquired. “A princess?”

Caroline looked mildly affronted. “No,” she said emphatically, her blond curls bouncing as she shook her head. “I’m a vampire slayer.”

“Of course. How foolish of me.” Sylvia raised her eyebrows at James. “Well, it seems to me that if you’re a vampire, and she’s a vampire slayer—”

James yelped and bolted away, the black cape of his old Halloween costume streaming behind him as he raced up the stairs as fast as his little legs could go. With a shriek of delight, Caroline set off in pursuit. Smiling, Sylvia watched the twins hurtle up both flights of stairs and disappear down the third-floor hallway. The playroom door slammed, startling her so that she nearly dropped the teacup after all. Cradling it in her palms, she shook her head, sighed more in amusement than exasperation, and continued on to the kitchen, where several of her dearest friends awaited her.

Friends—such a simple word, defined differently by everyone who used it. No single word of any definition could encompass all that the Elm Creek Quilters meant to Sylvia. In the twelve years since she had returned to the small rural town of Waterford, Pennsylvania, to accept responsibility for her family’s estate upon her elder sister’s death, the women gathered in the kitchen had become Sylvia’s colleagues and confidantes, her apprentices and her advisers. But more than that—they had become her family.

The sound of their laughter and the aroma of cinnamon-roasted apples drifted down the hallway toward her, and she quickened her pace, eager to find out what amused them so. Surely they weren’t laughing at poor, beleaguered Sarah, who had been engaged in a frenzy of cooking and baking since early that morning. In the spirit of Quiltsgiving, their annual winter camp session devoted to creating quilts for charity, Sarah had valiantly offered to take charge of preparing delicious meals befitting Elm Creek Quilt Camp’s sterling reputation for themselves and their twenty-four guests. Her friends eagerly and gratefully allowed Sarah to take the lead, although they had assured her they would pitch in if needed.

When Sylvia entered the kitchen, she found her friends doing exactly that. Stout Gwen, her gray-streaked auburn hair falling in a heavy curtain down her back, briskly chopped vegetables and, with a dramatic swirl of long batik skirts and the clinking of beaded necklaces, turned to slide them from the cutting board into a large stockpot bubbling on the stovetop. She was a professor of American studies at nearby Waterford College and the mother of another founding Elm Creek Quilter, Summer, a graduate student at the University of Chicago.

“One of these years I’ll join you for Quiltsgiving,” Summer had said wistfully during her holiday phone call. “Maybe when I’ve finished my dissertation. I’ll be with you in spirit.”

Of course she would be, Summer and their other dear friends who had left their circle of quilters but whose hearts remained at Elm Creek Manor—Bonnie, who had moved to Maui to run a quilter’s retreat and was engaged to a handsome Hawaiian; Judy, who had moved away to accept her dream job as a professor of computer engineering at the University of Pennsylvania; and Anna, their former chef, who had once ruled over the kitchen with kindness, generosity, and impressive skill.

It had been at Anna’s urging that Sylvia had agreed to install the dishwasher from which Maggie took clean plates and cups, her elegant hands graceful and assured. As she stacked the dishes in a nearby cupboard, a tortoiseshell barrette kept her long waves of light brown hair from falling into her oval face. At forty-three, Maggie was their newest teacher but not their youngest, although her coltish slenderness, the sprinkling of freckles across her nose and cheeks, and the shy cast to her soft hazel eyes often made her seem much younger. When Maggie glanced at the clock above the stove and sighed, Sylvia noted that it was almost time for Maggie’s daily phone call from Russell, her long-distance boyfriend. He was coming to visit later that week, and Sylvia suspected that Maggie was already counting the hours until his arrival.

On the other side of the kitchen, Diane, tall and blond and admirably fit for a mother of two grown sons, poured banana bread batter into a series of small loaf pans, occasionally scraping the sides of the bowl with a spatula or pausing to sip from her favorite oversized pink cappuccino mug. She scowled as if she had been dragged unwillingly out of bed only moments before, but Sylvia knew for a fact that she had been up for hours, as every Sunday morning Diane attended a six o’clock kickboxing class as faithfully as she attended ten o’clock Mass.

Sylvia heard Gretchen and Joe rummaging around in the pantry before she saw them. Gretchen, the compassionate soul who had conceived of Quiltsgiving, stood on a stepstool and stretched to retrieve a sack of sugar from the top shelf while her husband steadied her and murmured warnings for her to take care. Gretchen wore a thick taupe cardigan buttoned over a crisp white blouse, but the formality of her navy wool skirt was offset by her comfortable fleece slippers, their size exaggerated by her thin ankles. She was in her early seventies, with steel-gray hair cut in a pageboy and a frame that seemed chiseled thin by hard times, but she had lost the careworn look she had brought with her when she had accepted the teaching position with Elm Creek Quilts and had moved into the manor with her husband five years before. Gretchen and Joe, an expert restorer of antique furniture, were the most contentedly married couple of Sylvia’s acquaintance, with the exception of herself and her own dear Andrew.

At the thought of her husband, Sylvia glanced around the kitchen, not expecting to find him there but not entirely without hope that she might. He was probably outside helping Matt in the orchard or the barn, escaping the hustle and bustle of the kitchen for a few quiet moments of solitude before the quilt campers descended upon the manor.

Sarah turned away from one of the ovens, a steaming pan of apple-cranberry crisp in her oven-mitted hands, and her eyes met Sylvia’s. “I don’t know how Anna managed to feed fifty-plus quilt campers three meals a day five months straight year after year,” she declared wearily as she set the hot pan on a cooling rack. Sighing, she tucked a loose strand of reddish-brown hair behind her ear and brushed a dusty smear of flour from her right cheek with the back of the oven mitt. The gesture nudged her wire-rimmed glasses out of place, and Sarah impatiently pushed them back upon the bridge of her nose. “And I really don’t understand how she managed to be so cheerful doing it.”

“Anna was a professional chef,” Sylvia reminded her, then corrected herself. “Is a professional chef.” After all, Anna had not abandoned her profession when she resigned from Elm Creek Quilts.

“I’d be thrilled to have her back even if she never cooked for us again,” said Sarah glumly, taking a second pan of apple-cranberry crisp from the lower oven.

They all smiled at the improbability of that. On her all-too-rare visits to the manor, Anna reveled in whipping up delicious meals for her friends in the state-of-the-art kitchen she herself had designed. She was generous with her talents, as they all aspired to be, and she had regularly indulged them with their particular favorite dishes. Sylvia was partial to Anna’s apple strudel, which reminded her so much of her great-great-aunt Gerda Bergstrom’s celebrated recipe that with every bite, Sylvia imagined herself a child at Christmas again, surrounded by her parents and siblings and cousins, with snow falling softly against the windowpanes, a crackling fire in the hearth, and carols and laughter filling the air.

Snowy-haired Agnes’s blue eyes, bright and cheerful behind oversized pink-tinted glasses, lit on the folder tucked beneath Sylvia’s arm. “Are those for me?” she asked, setting aside her broom.

“Indeed they are,” said Sylvia, handing her the folder of registration forms. Long ago, Agnes had been married to Sylvia’s younger brother, although their romance had been cut tragically short when he had been killed in the service during the Second World War. Even though Agnes had remarried and had been widowed anew after many happy years, Sylvia would always consider Agnes her sister-in-law. “I made a few notes based upon the campers’ interests and hometowns, but I’ll leave the rest to you.”

Agnes nodded eagerly, seated herself in one of the comfortable booths, and spread out the forms on the table before her. Agnes always took charge of room assignments, a task everyone agreed she handled best. Although Sarah tried to accommodate every camper’s special requests as soon as their registration forms arrived in the mail or online, sometimes mistakes occurred, and other times the campers did not make their preferences known until they stood in the foyer. A quilter might need a first-floor room, only to discover that she had been given the key to a third-floor suite and that all first-floor rooms were booked. Two campers might decide on the way over from the airport that they wanted to room together, and roommate assignments would have to be shifted quickly and delicately, without hurting anyone’s feelings. Agnes, with her perfect combination of diplomacy and amiable resolve, deftly spun solutions that made everyone feel as if they had received the best part of the compromise.

While Agnes worked on room assignments, Sylvia carefully washed and dried her teacup, and just as carefully put it away. Then she tied on an apron and joined in the preparations for the Welcome Banquet, a celebration that marked the commencement of each new quilt camp session—and would inaugurate the fifth annual Quiltsgiving as well, although it was no ordinary week of quilt camp.

Within months of joining the Elm Creek Quilters, Gretchen had come to Sylvia with an intriguing idea for a way they could use their creative gifts to give back to their community. She proposed that they hold a special session of winter camp devoted to making quilts for Project Linus, a national organization whose mission was to provide love, a sense of security, warmth, and comfort to children in need through the gifts of new, handmade blankets, quilts, and afghans. The participating quilters would enjoy a week at Elm Creek Manor absolutely free of charge, but rather than working on quilts for themselves, they would make soft, comforting children’s quilts for Project Linus. Sylvia and the other Elm Creek Quilters found the idea absolutely ingenious. They quickly settled upon the week after Thanksgiving for their special camp session, and the season inspired the name.

In the months that followed, Gretchen founded a chapter of Project Linus in Waterford, which grew steadily over the winter and into spring as local quilting guilds spread the word and sounded the call for volunteers. Once a month the “Blanketeers” met at the manor to sew, knit, and crochet together, as well as to arrange the distribution of their handiwork. Elm Creek Manor became a drop-off site for donated quilts, afghans, and blankets, and every few weeks Gretchen would deliver them to the Elm Creek Valley Hospital, where they offered comfort to seriously ill children, and to the fire department, where they warmed youngsters rescued from fires and accidents.

The Elm Creek Quilters had hoped their ambitious project would result in many soft, bright, and beautiful quilts to warm and comfort mothers and children alike. But it was an untried experiment.

Only time would tell if it would succeed.

Before long, the time for planning and preparation ran out and Gretchen’s ambitious experiment was under way. Unlike Elm Creek Quilt Camp’s summer sessions, where the days were packed with classes, lectures, and seminars and the evenings full of scheduled entertainment, the first Quiltsgiving was more akin to a glorified, weeklong quilting bee. Fifteen volunteers brought their own projects in various stages of completion and worked diligently upon them, alone or in pairs or in small groups, in whatever cozy nook or corner of the manor they preferred. Three times a day the entire group met for meals in the banquet hall. After nightfall, when the campers’ eyes and fingers and backs had grown weary, Matt or Andrew would build a fire in the enormous ballroom fireplace and Gretchen would invite everyone to gather for a quiet, reflective hour before bed. They would sip tea or hot cider made from apples grown in the estate’s orchards, munch cookies, and chat about the work they had accomplished that day and their goals for the next.

By the end of the week, the Quiltsgiving Blanketeers had completed an impressive number of quilts to donate to Project Linus, which they proudly displayed at the Farewell Breakfast that brought Quiltsgiving to a close. Sylvia thought that would be a fine high note to end upon, but perfectionist Sarah insisted upon distributing evaluation forms, just as she did at the end of each week of summer camp. “It’s the only way to know if we’re meeting our guests’ expectations,” Sarah explained as she gathered up the forms after the last campers had departed.

“They got a free week at Elm Creek Manor, enjoyed three of Anna’s fabulous gourmet meals a day, and they made quilts for charity, exactly as advertised,” Diane replied, eying the stack of forms warily. “What unmet expectations could they possibly have?”

Privately Sylvia agreed. Still, the following afternoon she joined Gretchen and Sarah in the library to review the forms.

To Sylvia’s relief, the campers’ comments were overwhelmingly positive. Yet a pair of wishes—for structure and instruction—did emerge. Several campers, most of them new quilters, expressed disappointment that they had not learned any new techniques or patterns that week. Although they had known that they would be working upon their own projects, they were unaccustomed to having so many unscheduled hours to fill and had expected to have more opportunity to benefit from the knowledge and experience of the Elm Creek Quilters. “I didn’t think I’d have to stumble along on my own,” one anonymous camper had written.

The remark stung, but Sylvia took a deep breath and reminded herself that they had solicited the campers’ opinions and that constructive criticism would not benefit her if she became defensive.

Not so Gretchen. “We were always available to answer questions or offer help,” she protested. “I wasn’t aware that anyone was struggling.”

“Perhaps they were too shy to ask for advice,” remarked Sylvia. “We were hard at work on our own projects, except when we were preparing meals and such. Perhaps they were reluctant to interrupt.”

“Maybe it’s easier to ask us for help when we’re standing at the front of a classroom,” mused Sarah, returning her gaze to the evaluation forms. “We’ll have to figure out a way to remind our campers that the Elm Creek Quilters are teachers, first and foremost, one and all.”

“Would it be enough to tell them at breakfast each day?” asked Gretchen.

Sarah looked dubious. “Maybe.”

“Perhaps we could designate one or two Elm Creek Quilters each hour to circulate among the campers and keep an eye on things rather than working on their own projects,” said Sylvia.

“That couldn’t hurt,” said Sarah, but her slight frown and furrowed brow told Sylvia that she thought it wouldn’t suffice. Sarah soon returned her attention to the evaluation forms, but Sylvia knew her younger friend’s keen mind was already working on a solution.

That they would host a second winter camp for charity had never been in doubt; the abundance of warm, cozy quilts their campers had made for Project Linus the previous year was evidence enough that they should continue. The holiday season gave way to spring and National Quilting Day, followed by another busy summer of Elm Creek Quilt Camp, yet Sylvia, Sarah, and Gretchen never stopped thinking and talking together. By Labor Day and the end of the summer camp season, they finally concocted a solution to the problem that had bothered the novices among their Quiltsgiving guests: They would offer an optional, weeklong class, designed for beginners but suitable for anyone who wanted to learn a new, simple, attractive pattern that could be assembled with ease. Each morning they would tackle a different stage of the quiltmaking process, leaving the afternoons free for students to work on their projects individually and to seek extra help from their teachers. The Elm Creek Quilters would design quilts meant especially for giving—quick to put together but as beautiful and warm as any more complicated pattern. They could design a new Giving Quilt each Quiltsgiving to encourage volunteers to return year after year. Thus the most faithful volunteers would gradually build a repertoire of patterns they could draw upon whenever they needed to make a quilt on short notice or to make quilts to benefit their own local chapters of Project Linus.

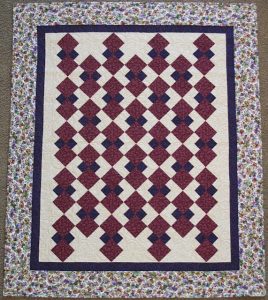

Sylvia declared that Sarah’s plan was inspired, and she asked for the honor of designing the first Giving Quilt. She chose the Bright Hopes block not only for its simple pattern—four rectangles framing a central square in the style of the popular Log Cabin block—but also for the rich symbolism of its name. All the Elm Creek Quilters had bright hopes for the second Quiltsgiving and for the many more winter camps they anticipated would follow.